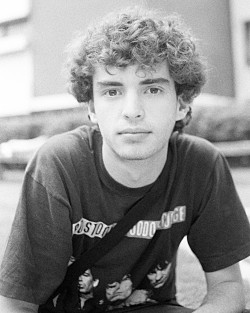

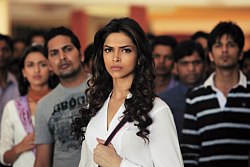

An auspicious and remarkably assured debut for Jonás Cuarón, the son of Alfonso, Año Uña started life as a photographic project documenting people as they went about their everyday lives. At the end of the assignment, Jonás and Eireann Harper completed an installation in which they mounted the thousands of photographic images in one room, ordered in scenes composed of shots. Consistencies began to emerge. The film’s narrative is completely fictional and can be summarised as an impossible romance between Molly (Harper), a 21-year-old American, and Diego (Diego Cataño,Temporada de patos), a Mexican in the throes of puberty. A beautiful mediation the passage from adolescence to adulthood, the film is a further signifier of the continued brilliance and diversity in Mexican cinema.

Popular on LondonNet

Jason Wood: Could start by talking about the genesis of the film?

Jonás Cuarón: The summer when I began taking the photographs Eireann had just finished writing an essay in which she explored the work La Jetée by Chris Marker. I had never seen this film before and was deeply inspired by it. We decided that we wanted to make a film in a similar format. In our approach to doing this there was one key difference to the work of Chris Marker. In La Jetée he wrote the screenplay first and then staged the photographs he took. In the case of Año Uña, we wanted to capture the photographs from a candid reality and from those photographs construct a fictional narrative, so we would be blurring the line between fiction and reality. After a year of taking photographs Eireann and I decided we wanted to do an installation in which we filled all the walls of a room in our university with the photographs I took. The idea was to give people the opportunity to approach all of the photographs and by seeing them construct their own narrative. When the installation was finished, I spent some time in the room, looking at the images and coming up with my own fictional narrative.

JW: How did the film then begin to develop from the initial photographs that you took and what themes and consistencies suggested themselves?

JC: Looking at the photographs, I began to see emerging patterns from which I constructed the narrative. The first thing that became obvious was that the people I photographed the most that year were my younger brother and my girlfriend. I decided that they would have to be my main characters, and the story became about a platonic relationship between a 21-year-old girl from the U.S. and a thirteen-year-old Mexican boy. Even though the narrative is fictional, many of the themes explored in the film were things that I observed while taking the photographs, and because I was constructing a film out of still images, I knew that time would be an important theme for me. That year my brother hit puberty and I could not help but notice how he moved through that transitional moment in life. The summer when I began taking the photographs Eireann came to Mexico with me, and I experienced through her what it is to be a foreigner, a stranger in a new place. That year my grandfather was diagnosed with cancer. The photographs of his surgery became an important backdrop through which I explored the concept of the passage of time and the impermanence of things.

JW: As I understand it every image in the film was captured using a stills camera. To what extent did this allow you to capture people at their most honest and relaxed and did this technique enable those that you shot to forget about the camera’s presence?

JC: The main concept of the film was to capture a very honest reality and later fictionalize it. I knew that the best way to approach this was with a stills camera since it would not intimidate my subjects. People are used to being photographed and after a couple of pictures they easily forget about the camera’s presence.

JW What other themes and subjects were you keen to tackle?

JC: The film explores the arbitrary boundaries that separate people from one another and which define us as individuals. In the film this boundaries are present in the age of the characters, in their culture, their nationality, and their language. Because the film is made with photographs, it inevitably explores the concept of time’s passing. That is why the film is structured around a year of the characters’ lives. The passage of time becomes very apparent in the character of the teenage boy, since adolescence is an age in which everything moves very fast. And it is also felt in the grandfather’s illness and death.

JW: The casting is also very significant on this film giving its background and the manner in which it evolved.

JC: Part of the concept of the film was to capture the essence of the people I photographed, of my family, so it was important for me to record the voices of the people seen in the photographs instead of casting actors to do the voice-overs. Unfortunately my grandpa could not speak after his surgery and I was never able to record his voice. I am lucky that my brother, Diego Cataño, had previous acting experience. For him this was a very interesting and different experience because he had to re-envision himself and give his character life only through voice.

JW: Mexico is blessed with skilled and very creative technicians and the sound design from Martín Hernández is tremendously important to Año Uña. How closely did you work with Martin and what contribution did you want the audio to make to what many may mistakenly see as a purely visual work?

JC: From the moment I ventured into this project I knew that the sound design would be crucial to giving the film life. When I had the first cut finished I showed it to Martin Hernandez, who I admire greatly, and he immediately decided to support the project. We worked together in creating a sound design that would allow the images to “move”. A common response people give to the film is that when they look back on it they remember it as if it had movement. I believe this effect is achieved thanks to the sound design. It was also important to create levels of sound to show variation between dialogue and inner monologue, which allows the narrative to move in and out of the characters’ heads.

JW: The production notes for the film make reference to the novel Elsinore by Salvador Elizondo.

JC: Salvador Elizondo was my grandfather, who plays a very big part in this film. Many of the themes explored in Año Uña are echoes of themes that he explored as a writer. He himself made a short film constructed out of still images called Apocalypse 1900.

JW: I’m struck by the translation of the film’s title, The Year of the Nail. Could you just explain its significance?

JC: A central theme of the film was the passage of time, so it was important for me to include in the title the concept of “the year”. Another very important theme is the boundary of language. That is why I decided to create a title with the letter “ñ”, since it is a letter that does not exist in English. “Año Uña” is a tongue twister, and it is a title that is really difficult to pronounce for anyone who speaks English. When I had to give the film’s title an English translation, I decided to use a literal translation to include the concept of time, and Diego’s ingrown toenail bookends the year.