Modern Painters: The Camden Town Group

The Tate Britain

13 February- 4 May 2008

Walter Sickert’s self-portrait hangs immediately to your right when you enter Tate’s Camden Town Group exhibition. It’s called The Juvenile Lead, and both words are perfect. It’s the kind of winking self-depreciation that would later allow him to paint the Edwardian equivalent of the O.J. Simpson debacle, The Camden Town Murder.

Popular on LondonNet

There was some outcry at Sickert’s flippant disregard for Art (as opposed to art), at his unimproved nudes, his sensational choice of subject. As the gallery’s explanations will tell you, Sickert would have found the whole thing hilarious. He was the kind of artist who defined his own ability, instead of letting critics or popular opinion do it.

In 1911, he gathered around him a group of painters who were heavily influenced by France’s Post-impressionists. They were the Camden Town Group, rejecting The Institution in their very name (Camden was, in those days, a bleak, un-cultured part of London), and a retrospective of their output is on display now for the first time in fifty years.

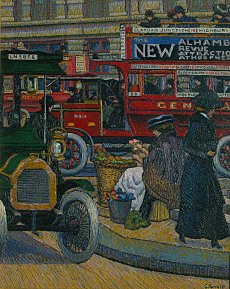

The gallery draws almost entirely from a core of the group – Spencer Gore, Harold Gilman, Charles Ginner, Robert Bevan, and Sickert himself. Ginner dominates much of the early rooms with Van Gogh homage and turn-of-the-century London staples leaping off the canvas in bright, thick color. Bevan makes an appearance with a series of light, farewell nods to the horse-taxi.

The gallery draws almost entirely from a core of the group – Spencer Gore, Harold Gilman, Charles Ginner, Robert Bevan, and Sickert himself. Ginner dominates much of the early rooms with Van Gogh homage and turn-of-the-century London staples leaping off the canvas in bright, thick color. Bevan makes an appearance with a series of light, farewell nods to the horse-taxi.

In the next room we move from London’s streets to its venues, as the group catalogue how the city spent its leisure time. Here we are introduced to Sickert, with his dark, earthy palate. Next it’s on to private lives. Sickert paints tension into a despondent marriage.

In the center of the gallery, high ceilings and white walls are replaced with a pair of short rooms painted in deep red and yellow, respectively. In the first, called ‘Sex’, the group’s take on the female form is revealed to be, for the time, almost completely groundbreaking and anti-romantic. Sickert, whose paintings dominate both central rooms, painted disinterested prostitutes on iron beds in decrepit rooms. A couple of his companions followed his lead.

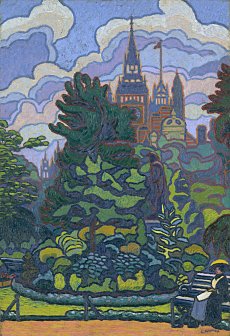

The effect of re-entering the bright, open rooms on the other side is impressive. We are greeted by the countryside, by Bevan’s geometric landscapes and Gore’s cubist fences.

The effect of re-entering the bright, open rooms on the other side is impressive. We are greeted by the countryside, by Bevan’s geometric landscapes and Gore’s cubist fences.

World War One hangs over the final gallery like a dark fog. There is an eerie desperation to many of these final installments, done in the last years of the Group’s existence. Early patriotism, such as in Gilman’s Leeds Market, gives way to tube stations as makeshift bomb shelters.

There is a footnote of a room at the exit, placing the paintings in context with books and posters from the period. It’s not necessary – the record of history is all there, set onto canvas by Britain’s most important Post-impressionists. This isn’t saying much, but Sickert, clearly an artistic giant, and the rest of his Group are probably worth a visit anyway.

– Kiernan Maletsky