Thriller

The Burnt Orange Heresy (15)

Review: Lying is easy when you tell the truth. That teasing line, spoken by one of the morally ambiguous characters in director Giuseppe Capotondi’s art world thriller, illustrates the silent tug of war between perception and reality at the heart of every human interaction. We accept information on face value and attribute worth based on the opinion of so-called experts rather than trusting our own judgment. The nonsensical title, shared by an unseen painting in the film, is intended to provoke hollow debate. “The critics, those ravenous dogs, can chew on it, searching for meaning,” explains the artist, played with avuncular glee by Donald Sutherland.

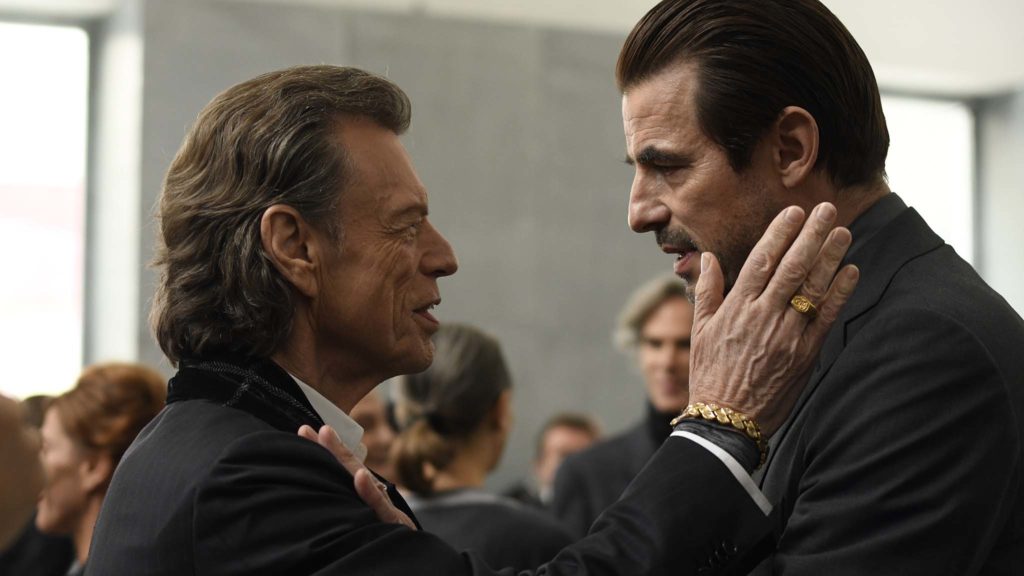

The meaning of Scott Smith’s script, adapted from the 1971 novel by Charles Willeford, takes almost an hour to come into focus and the rewards for our patience aren’t particularly bountiful. Claes Bang and Elizabeth Debicki catalyse gently simmering chemistry as fledgling lovers blinded by first impressions opposite an impish Mick Jagger as a connoisseur of beauty, who chews with delight on the film’s meaty one-liners. “Art can be such a harsh mistress, can’t she?” he smirks. One protracted scene – a leisurely drive along a lakeside road – is distracting for the wrong reasons. The driver and passenger spend agonisingly long stretches staring into each other’s eyes and completely ignore the winding road ahead. Logic dictates they should plough into oncoming traffic or plunge off the road into Lake Como.

Roguish art critic James Figueras (Bang) gallivants around Europe, armed with a well-rehearsed lecture on the power of persuasion. To illustrate his point, he invents a fake history for one of his own clumsily composed paintings and convinces small audiences of enraptured American tourists that his handiwork is a masterpiece crafted by a little-known artist in a Nazi concentration camp. Following one lecture in Milan, James beds pretty American attendee Berenice Hollis (Debicki) and invites her to accompany him to the sprawling Lake Como estate of art collector Joseph Cassidy (Jagger).

The charismatic host wastes little time offering James a private audience with one of America’s greatest living painters, who happens to reside in a guesthouse. “Think what a splash it would make – the first critic in more than 50 years to interview Jerome Debney!” tantalises Cassidy. In exchange for this career-revitalising opportunity, Cassidy insists James must procure him a priceless new work signed by Debney (Donald Sutherland).

The Burnt Orange Heresy is a slow-burning game of cat and mouse, which some audiences might playfully equate to watching paint dry. Capotondi maintains a pedestrian pace that makes the 98-minute running time feel considerably longer. A hastily contrived finale, dressed stylishly as a noir thriller, underwhelms despite the sweat-drenched desperation portrayed on screen.

Find The Burnt Orange Heresy in the cinemas

Animation

Wolfwalkers (PG)

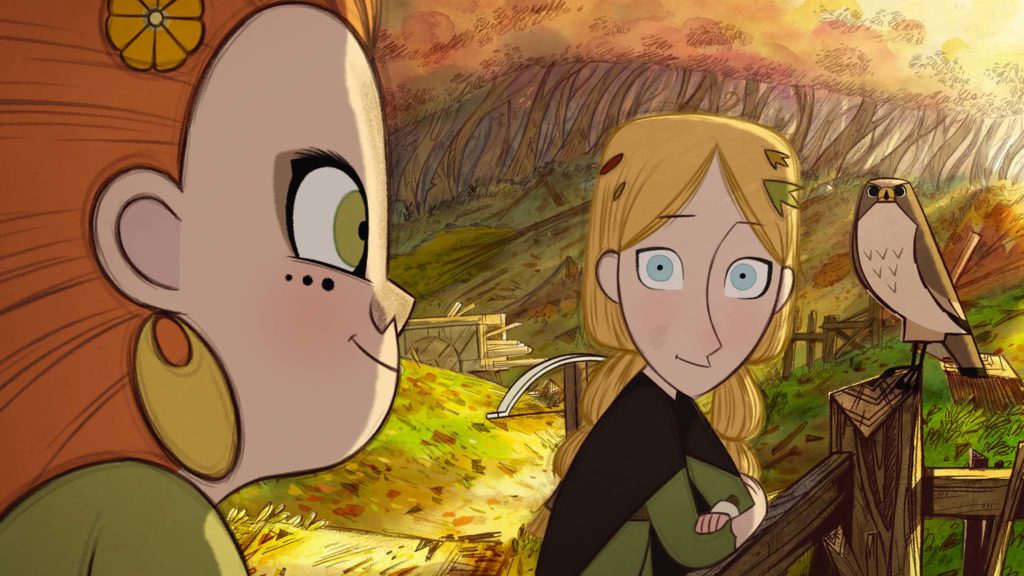

Review: Humanity’s combative relationship with Mother Nature sparks civil unrest in Tomm Moore and Ross Stewart’s enchanting animated fable. Distinguished by expressive hand-drawn visuals and emotionally rich storytelling, Wolfwalkers extends the winning streak of Kilkenny-based Cartoon Saloon, which deservedly snagged Oscar nominations for The Secret Of Kells, Song Of The Sea and The Breadwinner. A bold, angular aesthetic, which has become the studio’s trademark, is a handsome fit for a coming of age story set in mid-17th century Ireland – a time of magic and myth, religious fervour and forceful incursions by Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army.

Screenwriter Will Collins sows seeds of female empowerment and wilful defiance in his beguiling fairy tale, propagating a touching friendship between two girls on opposite sides of a bitter conflict. Energetic vocal performances from Honor Kneafsey and Eva Whittaker firmly anchor our affections to these spunky heroines as they wager their lives to protect the wilderness from destruction. Collins demonstrates a light touch with the environmentally conscious subtext and deftly navigates shifting political tides of the era without the need for a stodgy history lesson. One character’s eye-catching design draws comparisons to Princess Merida from Pixar’s 2012 animation Brave. While both films share themes of adventure and self-discovery, Wolfwalkers howls to its own rapturous beat. In 1650,

English forces led by a glowering Lord Protector (Simon McBurney) occupy the city of Kilkenny. Superstitious locals live in fear of wolves that roam the nearby woods. “What cannot be tamed must be destroyed,” growls the Lord Protector. He enlists swarthy hunter Bill Goodfellowe (Sean Bean) to exterminate the beasts. Bill’s young daughter Robyn (Kneafsey) yearns to hunt like her father but she is consigned to the scullery of the Lord Protector’s house.

The headstrong girl sneaks out of the city and encounters a flame-haired free spirit called Mebh MacTire (Whittaker), who belongs to a fabled tribe of wolfwalkers. When Mebh sleeps, her human body remains in peaceful slumber while her soul escapes in lupine form to wander the mortal realm. Alas, Mebh’s mother Moll (Maria Doyle Kennedy) is trapped in stasis because her wolf spirit has not returned. Robyn pledges to locate Moll and thwart the Lord Protector’s plan to reduce the woods to smouldering embers.

Wolfwalkers confidently casts a spell by nurturing the emotionally conflicted characters and allowing changes in their behaviour to happen organically, often with an outpouring of tears on screen. McBurney invokes fire and brimstone as the film’s tyrannical antagonist, tinging his scenes with palpable menace. Composer Bruno Coulais’ lyrical score harnesses the combined power of Irish folk band Kila and Norwegian singer Aurora, whose vocal trills set the tempo of Into The Unknown in Frozen II. Their sweet harmony epitomises the seamless blending of elements under pack leaders Moore and Stewart.

Find Wolfwalkers in the cinemas