Drama

Blue Bayou (15)

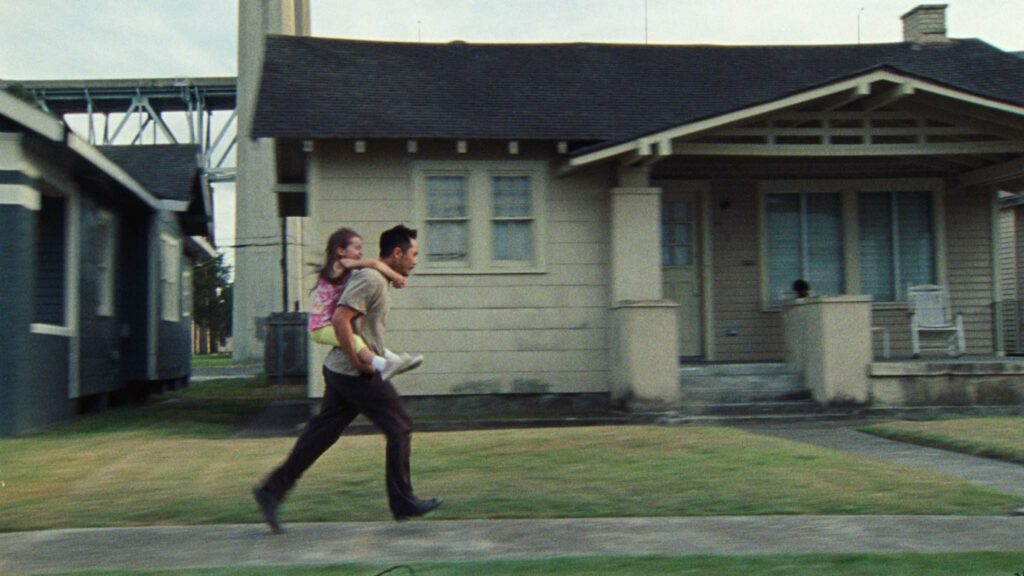

Review: Sharing its title with an achingly melancholic Roy Orbison song, which Oscar-winning lead actress Alicia Vikander performs on screen, Blue Bayou wrings melodrama from a real-life legal loophole that allows US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to deport some Korean-born men and women, who were adopted as children by American families before 2000. Victims can either accept their fate, return to the country of their birth and hope to return to America at a later date, or they can mount an appeal and offer compelling evidence to persuade a judge to let them stay. A legal challenge is expensive and fraught with peril: lose and the appellant forfeits any chance of returning to America.

A lawyer (Vondie Curtis-Hall) in the film soberly sums up the risk to an incredulous client (Justin Chon) and his wife (Vikander): “If he fights and loses, he can never come back.” The injustice of forcibly removing citizens in their 40s and 50s from a country they call home boils the blood of writer-director Chon’s script, tightly tethering our sympathy to a flawed lead character, who fights the decision and risks everything to stay in New Orleans. However, the writing is sometimes heavy-handed and big emotional beats, including a tense scene at an airport, feel like they have been engineered with trauma and tears in mind rather than allowed to develop organically from grave circumstances.

Tattoo artist Antonio LeBlanc (Chon) was born in Korea, adopted at the age of three and brought to the Louisiana bayou. He was reckless in his youth, stealing motorcycles with buddy Q (Altonio Jackson), and has a couple of felonies on his record which poses problems when applying for a second job. Antonio has turned his life around to provide for his wife Kathy (Alicia Vikander), who is pregnant with their first child, and Kathy’s daughter Jessie (Sydney Kowalske).

The girl’s biological father, Ace (Mark O’Brien), is a police officer, who feels aggrieved that Kathy is withholding access to his child in retaliation for him walking out on the relationship. The custody battle reaches a flashpoint when Ace’s partner Denny (Emory Cohen) abuses his badge to arrest Antonio and place him in the custody of ICE.

Blue Bayou is a labour of love for Chon, culminating in photographs of real-life adoptees who have faced the same nightmarish scenario as Antonio. The writer-director deals sensitively though not always subtly with a charged issue and in front of the camera, he delivers a strong performance and catalyses convincing screen chemistry with Vikander and Kowalske. A prosaic secondary plot involving a terminally ill Vietnamese refugee (Linh Dan Pham) is padding without a satisfying emotional pay-off.

Find Blue Bayou in the cinemas

Romance

Boxing Day (12A)

Review: The origins of Boxing Day – the day after Christmas – are boisterously disputed by historians but many theories concern physical boxes filled with gifts, food or money as donations or shows of appreciation to the less fortunate, servants, tradespeople and poor parishioners. In writer, director and actor Aml Ameen’s festive frolic, December 26 is a date steeped in heartache and regret, when a son travels halfway around the world in response to his parents’ unexpected announcement that they plan to divorce.

Christmas is a time for giving… up on relationships, but like many frothy romantic comedies filled with attractive yet insecure middle-class people in the throes of competing emotional crises, this Boxing Day ultimately overflows with tidings of comfort and joy. Ameen’s script, co-written by Bruce Purnell, is disappointingly light on laughs and some of the biggest are hand-me-downs. A tense game of dominoes between love rivals is reminiscent of the combative mah-jongg scene in Crazy Rich Asians, and a male protagonist follows Andrew Lincoln’s lead from Love Actually and begs his girlfriend’s forgiveness with hand-written words of apology on a deck of A3 white cards.

The grand gesture falls flat, causing his sister to quip, “Bruv, them things don’t work no more!” The same charge could be levelled at sections of Ameen’s film, which maintains a light effervescence but never pops its cork. Ironically, it’s when characters shed the goofiness and get serious that they make the greatest impact, like when a mother articulates to a white boyfriend the invisible yet indelible mark left by her experience of raising black children in the 1980s and 1990s.

Two years after his parents Shirley (Marianne Jean-Baptiste) and Bilal (Robbie Gee) announced their divorce during Boxing Day celebrations, London-born novelist Melvin McKenzie (Aml Ameen) has relocated to Los Angeles with high-flying girlfriend Lisa (Aja Naomi King). A wedding proposal doesn’t go as planned and Lisa agrees not to wear the ring until Melvin ‘surprises’ her with another perfect declaration on bended knee.

In the meantime, he faces an awkward homecoming to promote his latest book and agrees to take Lisa with him to meet his dysfunctional British-Caribbean kin. Back in London, Melvin trades barbs with his sister Aretha aka Boobsy (Tamara Lawrance), who works as a personal assistant to old flame Georgia (Leigh-Anne Pinnock). When Lisa discovers Melvin used to date a singing superstar, the relationship falters. “It’ll be all right in the end. If it isn’t all right, it’s not the end,” Bilal soothingly advises his son.

Boxing Day is all right in the end thanks to larger-than-life performances from a predominantly British cast including the film acting debut of Pinnock from Little Mix. Ameen’s ambition exceeds his grasp when it comes to character development. He juggles the love stories of three different generations and only catches one cleanly.

Find Boxing Day in the cinemas

Drama

C'mon C'mon (15)

Review: When comedian and actor WC Fields reportedly coined the showbusiness mantra to never work with children or animals, he clearly wasn’t referring to 12-year-old British actor Woody Norman. The cherubic wunderkind sports a flawless American accent and merrily scene-steals from Joaquin Phoenix in writer-director Mike Mills’ bittersweet and life-affirming picture, which explores the bond between a radio producer and his precocious nephew.

Shot in lustrous black and white (a stylistic choice in vogue this year), C’mon C’mon charms and breaks our hearts through delicately staged conversations between the characters, which have the casual flow of documentary filmmaking rather than scripted drama. That naturalistic vibe is enforced by footage of Phoenix’s protagonist interviewing real children from different cities across America about their feelings and fears. Each non-scripted yet heartfelt train of thought is captured in close-up as the Oscar winner brandishes a microphone and listens intently through his headphones.

The children’s articulate and occasionally humorous insights are tinged with hope. Out of the mouths of babes come simple, unvarnished truths. Charming chemistry with Norman galvanises every scene, whether the two actors are playfighting, riffing off each other or digging deep into the emotional wounds of a boy who has lost a positive male role model in his life to a mental health crisis. Mills maintains a slow, steady pace that allows on-screen camaraderie to develop or fray realistically while we silently reflect and shed a tear on our own wonder years.

New York-based audio producer Johnny (Phoenix) is in Detroit, interviewing young people with colleagues Roxanne (Molly Webster) and Fernando (Jaboukie Young-White), when he receives an urgent telephone call from his estranged sister Viv (Gaby Hoffmann). She implores Johnny to travel to Los Angeles to take care of her nine-year-old son Jesse (Norman) for a couple of weeks while she supports her ex-husband Paul (Scoot McNairy) as he contends with bipolar disorder.

Unprepared for temporary guardianship, Johnny muddles through each day with Jesse, allowing the inquisitive tyke to use his microphone and recording equipment to capture the cacophony of a city in motion. When Paul’s mental state worsens, Johnny agrees to take his nephew on the road to New Orleans for more radio interviews and the bond with Jesse deepens. Meanwhile, a mentally and physically exhausted Viv makes regular phone calls to Johnny to track her boy’s progress. “I just want Jesse to have his dad,” she quietly confides.

C’mon C’mon is a delicate study of the complexities of youth, reflected in tiny moments between Johnny and Jesse as they seek a deeper understanding and appreciation of each other. Every minute of Mills’ film is heartbreakingly beautiful and precious. This boy’s life is truly wondrous.

Find C'mon C'mon in the cinemas

Horror

Resident Evil Welcome To Raccoon City (15)

Review: In the late 1990s, I (mis)spent many fitful hours with a dwindling supply of ammunition hunting zombies around the dimly lit Spencer Mansion in the PlayStation survival horror game Resident Evil. The vicarious blood-spattered thrills of that first title spawned countless imitators and laid the groundwork for a sprawling franchise that continues to this day, encompassing video games, films, TV series, novels and comic books.

In 2002, Northumberland-born director Paul WS Anderson delivered the first instalment of the Resident Evil film adaptations and now, writer-director Johannes Roberts reboots the zombified carnage with an origin story based on the plots of the first and second games. Pivotal characters including Claire Redfield, her brother Chris, Jill Valentine, Leon S Kennedy and Albert Wesker are faithfully brought to life along with a zombie dog, infected crows and hulking humanoid soldier Tyrant. An additional scene buried in the end credits adds another familiar face to the fold.

Once the buzz of recognition subsides, Roberts’ picture reduces to a predictable cycle of showdowns with the infected, grisly character deaths and recreations of key set-pieces including the subterranean escape train. Digital effects aren’t convincing and pacing is leaden, even with an onscreen countdown to 6am when an entire community will be levelled to contain the outbreak.

Claire Redfield (Kaya Scodelario) hitchhikes through torrential rain to Raccoon City to find her estranged brother Chris (Robbie Amell), a member of the Special Tactics And Rescue Service (STARS) Alpha Team attached to the local police department. She warns him about the nefarious activities of the Umbrella Corporation, which managed the orphanage where they grew up under the dubious care of Dr William Birkin (Neal McDonough). Claire’s arrival coincides with a Chernobyl-style leak of the T-virus from a deserted Umbrella Corporation facility. Residents mutate into crazed predators with an insatiable hunger for flesh.

Chief Irons (Donal Logue) despatches Chris and the rest of STARS comprising Jill Valentine (Hannah John-Kamen), Albert Wesker (Tom Hopper), Richard Aiken (Chad Rook) and helicopter pilot Brad Vickers (Nathan Dales) to search the mansion of Umbrella Corporation president Oswell Spencer. Meanwhile, Raccoon City Police Department rookie Leon S Kennedy (Avan Jogia) teams up with Claire to neutralise the slavering hordes.

Resident Evil: Welcome To Raccoon City is on par with Anderson’s first outing including a few cheap jump scares. Scodelario pales next to Milla Jovovich’s competing angel of death from almost 20 years ago but she wears Claire’s signature red jacket with stony-faced conviction. The script achieves unintentionally hilarity when Chris soothes a critically injured cop, who has just had their throat ripped out, by chirruping: “You’ll be fine. This is nothing!” If you believe that, you’ll believe Roberts’ film warrants a sequel.

Find Resident Evil Welcome To Raccoon City in the cinemas

Comedy

Silent Night (15)

Review: Stiff upper lips bead with sweat when Mother Nature strikes back at humanity for polluting the planet in Camille Griffin’s blackly humorous apocalyptic horror. Tidings of discomfort overflow deliciously when old school chums convene at a country house for a final Christmas together replete with roast turkey and charades before a toxic cloud wipes pernicious homo sapiens off the surface of the Earth for good.

Combining the nostalgic reminiscence of Peter’s Friends with the fantastical gloom of Lars von Trier’s end-of-the-world drama Melancholia, Silent Night ponders how each of us might respond to the promise of a slow, agonising death: by stoically carrying on and hoping the doom mongers are wrong or by actively taking precautions to slip away painlessly before the countdown to climate catastrophe hits zero. Birdy’s arrangement of the traditional carol Silent Night, which the Hampshire-born singer-songwriter performs as a haunting lament on the last breaths of wind before doomsday, is a suitably chilly accompaniment to the moral quandary.

Tonal shifts from mirthful to morose and macabre occasionally jar as writer-director Griffin witnesses the implosion of polite, privileged society through the eyes of a boy, who dares to question the reliability of public information and is openly furious at his parents for signing his death warrant. With so many characters to flesh out in just 90 minutes, the script operates at surface level for some of the assembled throng and the resolutions of their inner turmoil – an alcoholic trying to maintain sobriety, an expectant mother consumed by guilt about the prospect of killing her unborn child – feel rushed.

Nell (Keira Knightley) prepares a last supper for old school friends before a lethal gas cloud arrives. The government has prescribed suicide pills called Exit to every legal citizen and Nell and husband Simon (Matthew Goode) have sufficient quantities for their family including sons Art (Roman Griffin Davis), Hardy (Hardy Griffin Davis) and Thomas (Gilby Griffin Davis).

Sandra (Annabelle Wallis), husband Tony (Rufus Jones) and daughter Kitty (Davida McKenzie) are first to arrive, closely followed by Bella (Lucy Punch) and her clueless girlfriend Alex (Kirby Howell-Baptiste). Once doctor James (Sope Dirisu) and American girlfriend Sophie (Lily-Rose Depp) decant from his sports car, the prosecco flows and differences of opinion about suicide divide the guests. “I can’t do post-apocalyptic monochrome,” quips designer-labelled Bella.

Shot before Covid, Silent Night acquires unfortunate new layers of (mis)interpretation in the current climate of vaccine drives to keep pace with a mutating virus. The ensemble cast toss verbal grenades at each other with glee, conjuring the appearance of familiarity as years of suppressed frustration bubble to the surface like fizz in flutes of prosecco. Bottoms up as we all fall down.

Find Silent Night in the cinemas