Comedy

Anora (18)

Review: In a memorable scene from the fairy tale romance Pretty Woman, Julia Roberts’ smartly dressed working girl returns to the Rodeo Drive boutique that refused to serve her and playfully taunts snooty sales staff with the sizable commissions they lost because of their rudeness. “Big mistake… huge!” she grin, arms laden with designer label shopping bags. It would be a big mistake… no huge, to neglect writer-director Sean Baker’s deservedly Oscar-tipped comedy drama, which relocates the same wish-fulfilment fantasy to the strip clubs of Manhattan.

Unlike its predecessor, Anora doesn’t shy away from graphic scenes of sex, drug-taking and wild abandon between a wealthy client and an erotic dancer, played with lip-smacking gusto by Mikey Madison. From the moment her Pretty Fierce And Filthy Woman appears performing a lap dance in orgasmic slow motion, Madison blows through Baker’s film like a category-five hurricane and holds our attention in a chokehold between her thighs.

Resistance is futile, whether her unstoppable force of nature is breaking the nose of one thug who attempts to restrain her or clawing out the eyes of a jealous rival who tries to steal her high-spending customer. Frenetic, hilarious and deliriously destructive set pieces are briskly edited and deliver repeated jolts of adrenaline and dopamine, accompanied by a pulsating soundtrack that opens improbably – yet fittingly – with a rousing chorus of Brit pop trio Take That’s anthem Greatest Day.

Brighton Beach stripper Anora Mikheeva (Madison), known to friends as Ani, works at a high-end club frequented by men with more money than sense. She leverages her knowledge of the Russian language to befriend Ivan Zakharov (Mark Eydelshteyn), 21-year-old playboy son of a Russian oligarch who misbehaves without consequence because his godfather Toros (Karren Karagulian) and hired henchmen Garnick (Vache Tovmasyan) and Igor (Yura Borisov) are always on hand to clean up his messes.

Ivan becomes smitten with Ani and pays her 15,000 US dollars to pose as his girlfriend for a week, Pretty Woman-style. At the end of the agreement, the couple impulsively elope to Las Vegas to marry. When Ivan’s furious parents (Darya Ekamasova and Aleksey Serebryakov) learn of the nuptials on social media, they fly to the United States to demand an annulment.

Anora is a wildly profane, whoop-inducing and tender-hearted blast, and continues Baker’s compassionate, multi-faceted depiction of marginalised communities, immigrants and sex workers exemplified in his films Tangerine, The Florida Project and Red Rocket. The script mines ribald humour and touching sentiment from on-screen chaos, captured on a roaming handheld camera that harnesses the boundless energy of Madison and co-stars. Plot machinations ultimately deliver a shattering emotional release that delivers a swift kick to the nether portions of a neat, conventional happy ending. Some princesses proudly wear stripper heels and not every prince needs to be charming.

Find Anora in the cinemas

Drama

Blitz (12A)

Review: A monochrome photograph in the archives of the Imperial War Museum of a small black boy in a sea of child evacuees on July 5 1940 inspires Oscar-winning writer-director Steve McQueen’s dramatisation of the wartime bombing of the English capital by Hitler’s Luftwaffe, glimpsed predominantly through the eyes of a nine-year-old boy from a mixed ethnic background. McQueen’s episodic script conflates real-life people and events from 1940 and 1941 such as the bombing of Balham tube station and a direct hit to the Cafe de Paris during a big band performance. Jewish activist Mickey Davis, who led a volunteer-run shelter for East End families displaced by the bombing, features heavily in one plot strand.

Sequences of munitions raining down on the city and a plane crashing into dockside buildings are breathlessly staged but ghosts of cinema past haunt Blitz and McQueen’s vision feels underwhelming by comparisons. John Boorman’s semi-autobiographical coming-of-age story Hope And Glory captured the same time period with deeper emotion, the flooding of a London Underground station was staged more thrillingly by director Joe Wright in Atonement, and the looting of the dead by a gang of grotesque ne’er-do-wells picks a pocket or two of Oliver Twist.

The constant source of light is 11-year-old newcomer Elliott Heffernan. Discovered during an open casting call, the first-time actor delivers an emotionally raw performance in the midst of directorial brio, which helps McQueen to scrub away the whitewash from British wartime history. Heffernan plays George, who is begrudgingly evacuated to the countryside from the home he shares with mother Rita (Saoirse Ronan) and grandfather Gerald (Paul Weller) in Stepney, east London. The tyke leaps off the moving train, a few miles outside of the station, and make his way back home. En route, George encounters a kind-hearted Nigerian air raid warden named Ife (Benjamin Clementine) and menacing gang leaders Albert (Stephen Graham) and Beryl (Kathy Burke).

Blitz is McQueen’s weakest fiction inspired by historical source material and is not on a par with Hunger, 12 Years A Slave or the Small Axe collection. The filmmaker’s verve and artistic flourishes are impressive such as reflecting a runaway horse backlit by flames in the pupils of George’s eyes or a graceful whirl around the Cafe de Paris before the bomb hits, captured as a single tracking shot. However, the gift inside this beautiful wrapping is insubstantial.

Heffernan dominates his scenes and catalyses lovely screen rapport with Ronan. Supporting performances add flecks of colour but are often throwaway. Hayley Squires’ cockney munitions factory rabble-rouser loses her voice while Harris Dickinson’s firefighter, who saves Ronan’s songbird from a collapsing brick wall, barely registers. McQueen’s picture consistently smoulders but doesn’t catch light.

Find Blitz in the cinemas

Thriller

Heretic (15)

Review: Since his first utterance of a plummy f-bomb in the fraught opening scene of Four Weddings And A Funeral, Hugh Grant has traded heavily on the archetype of a bumbling, confused yet charming British gentleman with clumsily articulated amorous intentions. Such was the dazzling brilliance of his adorably self-deprecating upper-class clown, Four Weddings co-star Andie MacDowell’s love interest was famously blinded to the torrential downpour that greeted his declaration of love at the end of the film: “Is it still raining? I hadn’t noticed…”

Another deluge clatters on windowpanes in Heretic but the sun shines brightly on Grant, who retains a soothing British accent but gleefully subverts his nice guy persona to play the most deadly predator of all: one who hides in plain sight, clad in a patchwork cardigan with a Bless This Mess embroidery on the living room wall, and cajoles lambs to the slaughter with razor-sharp rhetoric. He is both the icing and the booze-spiked cherry on top of a delicately flavoured cake mixed by writer-directors Scott Beck and Bryan Woods, which rises perfectly for the opening hours then falls a little flat when weaponised words are traded for a familiar array of deadly blades.

The filmmaking duo, who co-wrote the first instalment of A Quiet Place, conjured a literal boogeyman in their previous film based on a Stephen King Short story. Here, they unleash a sociopathic scholar, who plays diabolical minds games with two Mormon missionaries, challenging their notions of belief, faith and devotion and inviting the discombobulated prey to fling themselves into the jaws of various intellectual bear traps. Tight close-ups of the actors – the film is essentially a three-hander – are unsettling by design.

His unsuspecting victims are Sister Barnes (Sophie Thatcher) and Sister Paxton (Chloe East) from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The young women knock at the door of Mr Reed (Grant), armed with literature and compelling scripture to shepherd their host into the flock. Rules dictate that a woman must be present in a home for the Sisters to enter. “My wife has a pie in the oven,” warmly explains Mr Reed, beckoning Barnes and Paxton out of the rain to play a deadly theological game of cat-and-mouse.

Heretic challenges the structural foundations of most mainstream religions as Grant’s wolf in cosy knitwear delivers his diabolical sermon. Thatcher is a compelling foil for Grant’s polite menace and their scenes fizz deliciously like droplets of water hitting smoking, hot oil. One traditional jump scare and visible gore are reserved for a loopy final reckoning that leaks tension at an alarming rate but avoids implosion thanks to Grant’s powerhouse portrayal.

Find Heretic in the cinemas

Thriller

Juror #2 (12A)

Review: At the tender age of 94, Oscar-winning filmmaker Clint Eastwood probes the malleability of American justice in a solid but contrived courtroom drama penned by Jonathan Abrams, which plays out like a moral quandary torn from the pages of a John Grisham novel. Indeed, the central character of Grisham’s robust thriller The Runaway Jury also serves as Juror #2 for a high-profile trial, and both pictures stoke moderate tension by exploring the tangled lives of 12 men and women in the deliberation room charged with thoughtfully weighing the evidence.

Nicholas Hoult is well cast in Eastwood’s picture as a recovering alcoholic grieving the loss of twins during pregnancy. A noose tightens slowly around his character’s neck in Abrams’ script and his AA sponsor (Kiefer Sutherland) just happens to be a lawyer, who can distil pithy nuggets of legalese to counsel against any course of action that might expedite the running time. There are no last-gasp twists or surprise witnesses, nor are there any clear-cut heroes or villains, just morally conflicted people in the wrong place at the wrong time, torn between nobility and self-preservation.

Eastwood’s unfussy and assured direction glides through the trial without fanfare or distraction from an impressive ensemble cast including JK Simmons and Leslie Bibb as fellow jurors. The dramatic fulcrum is magazine writer Justin Kemp (Hoult), who is sequestered to serve on a murder trial, passing judgment on brutish defendant James Sythe (Gabriel Basso). Sythe is accused of killing his hot-headed girlfriend Kendall Carter (Francesca Eastwood) one year ago, following a public fight in a bar.

Ambitious prosecutor Faith Killebrew (Toni Collette) knows a guilty verdict could swing an impending election for district attorney in her favour. “This case is my campaign,” she private confides. Public defender Eric Resnick (Chris Messina) refuses to accept her plea deal – voluntary manslaughter with a recommendation for 20 years in prison – because his client is innocent and wants his day in court. Justin listens intently to testimony and faces an agonising moral dilemma: he was at the same bar as James and Kendall that rain-lashed night, and struck something on the road during the drive home – perhaps a deer, perhaps his girlfriend. A belated confession by the juror could set Sythe free but Justin has a doting wife (Zoey Deutch) at home in the third-trimester of a high-risk pregnancy.

Juror #2 is a straightforward and entertaining procedural drama, which spends almost two hours putting Justin through an emotional wringer before Sythe stands in court to hear his verdict. There are echoes of 12 Angry Men with Justin as the sole voice for acquittal and Eastwood allows dialogue and performances to drive the robust middle act. Hoult exudes nervousness and culpability for almost the entire film, which would be detected in a courtroom setting where everyone is under intense scrutiny. Eastwood’s quietly engrossing picture stands guilty of many things – contrivance, predictability, ruthless efficiency – but realism isn’t one of them.

Find Juror #2 in the cinemas

Drama

Small Things Like These (12A)

Review: Adapted by playwright Enda Walsh from Claire Keegan’s award-winning novel, Small Things Like These preaches about the silent complicity of a close-knit 1980s Irish community, which carries the invisible scar of generational trauma inflicted by a Magdalene laundry. The church-controlled institution confines women and girls and compels them to work as penitence for the sinful transgression of falling pregnant outside of wedlock. Terrified daughters vanish, disowned by parents to the mercy of steely-eyed nuns, who ignore tearful pleas for compassion and sell the newborns to foster families. Screams for help carried on the wind are heard but ignored by God-fearing townsfolk, who rely on the church to educate their children.

Belgian director Tim Mielants’s melancholic drama challenges one soft-hearted family man (Cillian Murphy) to turn a blind eye after he witnesses the debasement of young charges in the care of Mother Superior, played with an intense, soul-scorching stillness by Emily Watson. In one barnstorming scene, the father cowers in the sister’s presence as she adds five £10 notes to a handwritten Christmas card for his wife and calmly licks the envelope shut: “That’s us done, I’d say.”

Murphy’s tightly clenched performance, underscored by immersive sound design that captures every tremulous intake of air to soothe frayed nerves, is in stark contrast to his charismatic, Oscar-winning portrayal of J Robert Oppenheimer.

When he was 12 (played by Louis Kirwan), coal merchant Bill Furlong (Murphy) witnessed his mother (Agnes O’Casey) die suddenly while working for Mrs Wilson (Michelle Fairley). Raised by the wealthy war widow, one of the few women who could do what she pleased, Bill grew up with a deep-rooted need to help others. Now a father to five daughters, Bill is fiercely protective of his brood so when he witnesses horrors at the local convent, he faces an agonising moral quandary. “If you want to get on in this life, there are things you have to ignore,” calmly counsels his wife Eileen (Eileen Walsh). Local publican Mrs Kehoe (Helen Behan) echoes the cautionary sentiment, warning Bill that the sisters have fingers in every pie and if he casts aspersions, he could sound a death knell for his coal yard. “Keep the bad dog with you and the good dog won’t bite,” she strongly urges.

Small Things Like These is a measured and absorbing contemplation of the cruelty that takes root like a weed when an entire community averts its gaze under the guise of self-preservation. At every turn, Walsh’s script practises restraint, addressing the same historical injustices as The Magdalene Sisters and Philomena without explicitly depicting abusive behaviour on screen. Murphy is mesmerising, single tears occasionally rolling down his cheek bones as tight-lipped turmoil crests behind a fracturing emotional dam. Mielants concludes his deliberately slow-paced film before the walls are breached.

Find Small Things Like These in the cinemas

Documentary

Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story (12A)

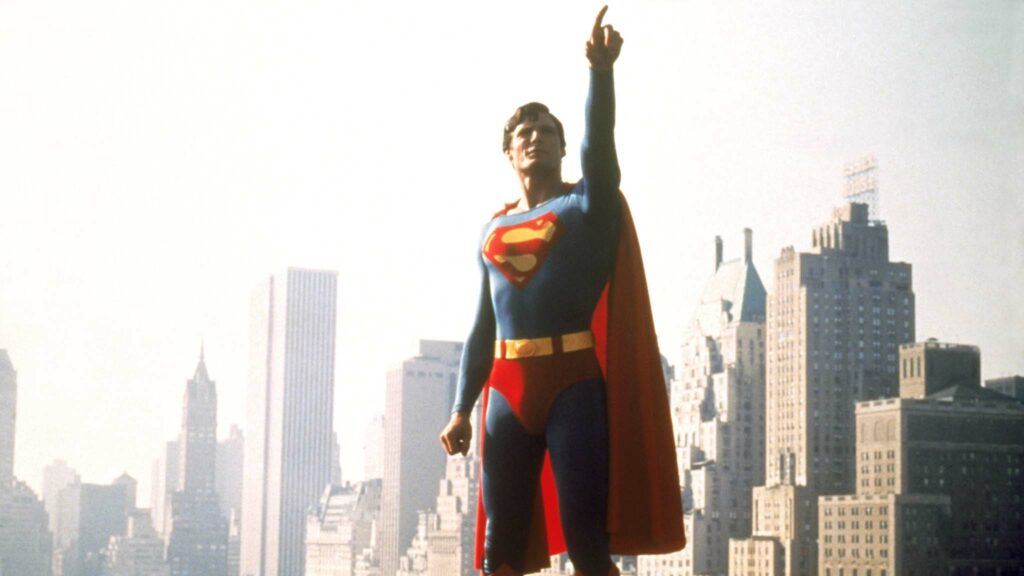

Review: Created by writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, Superman first took flight in 1938 on the pages of DC Comics but for many generations, New York-born actor Christopher Reeve was – and always will be – Kryptonian outcast Kal-El and his earthbound alter ego, bespectacled Daily Planet reporter Clark Kent. Reeve was largely unknown in 1978 when he landed the lead role in Superman: The Movie, directed by Richard Donner.

Robert Redford had turned down the part and singer-songwriter Neil Diamond was apparently considered for the Man of Steel before producers took a leap of faith on Reeve, surrounding their fresh-faced lead with established names including Gene Hackman as Lex Luthor and Marlon Brando as Superman’s biological father Jor-El.

A moving and affectionate feature-length documentary portrait directed by Ian Bonhote and Peter Ettedgui relives the glory days of Reeve before and after the freak riding accident on May 27 1995, which left him paralysed and reliant on medical intervention to continue his work on screen and garner headlines as a passionate disability rights activist.

Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story is festooned with intimate home movies including the heart-rending moment when Reeve’s second wife Dana utters the words, post-accident, that he claimed saved his life: “You’re still you. And I love you.” Testimony from celebrities Glenn Close, Susan Sarandon, Jeff Daniels and Whoopi Goldberg offers glimpses of the family man behind the Hollywood glitz but the most moving reminiscences are reserved for a lifelong friendship with Robin Williams, who also studied theatre at The Juilliard School in New York in the early 1970s. “I’ve always felt that if Chris was still around, Robin would still be alive,” solemnly confides Close.

The first extended film interviews with Reeve’s three children, Matthew, Alexandra and Will, about their father pluck heartstrings as they share memories of the man they called Dad but were forced to share with millions of clamorous fans. Lumps in throat are inevitable when youngest son Will reminds us that he was 12 when his father died and he became an orphan before his 14th birthday, losing his maternal grandmother then his actress mother Dana to lung cancer. “A hug from my mom was like being wrapped up by the sun,” Will recalls on screen.

Bonhote and Ettedgui’s film affords sufficient screen time to Reeve’s relationship with British modelling agent Gae Exton and its subsequent breakdown and also illuminates how Reeve repeated cycles of harsh parenting from his impossible-to-please father by skiing far ahead of 10-year-old Matthew and six-year-old Alexandra on challenging slopes. Every frame of Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story, expertly edited by Otto Burnham, underlines the personal relationships that prevented the actor from falling victim to the Kryptonite of fame and ambition. Superman made him, mortals saved him.

Find Super/Man: The Christopher Reeve Story in the cinemas