Horror

Old (15)

Review: In 2000, M Night Shyamalan guided 11-year-old Haley Joel Osment to a deserved Academy Award nomination as a reluctant medium, who stares into the eyes of Bruce Willis’s disbelieving child psychologist and confides, “I see dead people”. Among six Oscar nods for the film, there were two for Shyamalan’s direction and ingenious script replete with a trademark final reel twist, which he has attempted with diminishing returns in subsequent phantasmagorical nightmares. More than 20 years later, Shyamalan completes the stuttering odyssey from The Sixth Sense to The Complete Nonsense with an outlandish holiday from hell, based on Pierre Oscar Levy and Frederik Peeters’ graphic novel Sandcastle.

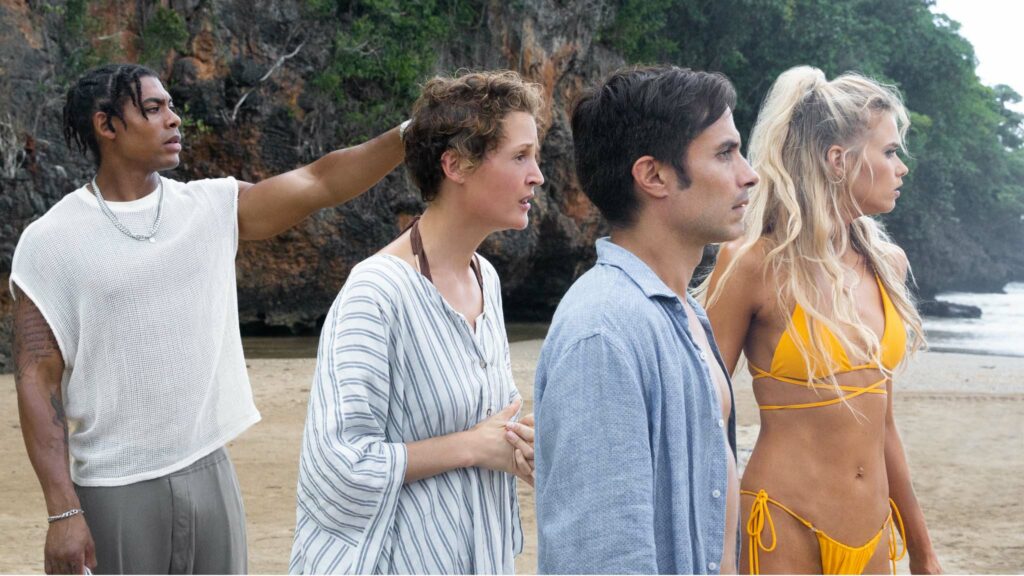

Toying sadistically with the flow of time, Old squanders a neat dramatic conceit – a beach where visitors age one year for every 30 minutes spent by the water – with bewildering directorial choices, crude expository dialogue and sluggish pacing that makes it feel like we’re wilting at the same ferocious rate as doomed characters. A gifted international cast including Gael Garcia Bernal, Vicky Krieps and Rufus Sewell are off-kilter, presumably by design, delivering some of their lines without any emotional connection to co-stars and others with derisory overwrought abandon. If there is a method to Shyamalan’s heavily stylised madness, it fails to manifest in 108 minutes of screen time, and certainly not before a convoluted finale that thankfully avoids any ridiculous rug-pulling.

Museum curator Prisca Capa (Krieps) and her actuary husband Guy (Bernal) take their 11-year-old daughter Maddox (Alexa Swinton) and six-year-old son Trent (Nolan River) to a tropical island sanctuary, which she found online. The children are excited when resort manager Nils (Gustaf Hammarsten) offers to arrange a special excursion to a hidden private beach on the same side of the island as a natural preserve. “I only recommend it to certain guests,” smiles Nils.

Another family, comprising cardiothoracic surgeon Charles (Sewell), younger wife Chrystal (Abbey Lee), six-year-old daughter Kara (Kyle Bailey) and his mother Agnes (Kathleen Chalfant), join the Capas on the short minibus ride to a perfectly secluded expanse of sand enclosed by rocky cliffs. Celebrated rapper Mid-Sized Sedan (Aaron Pierre), nurse Jarin (Ken Leung) and his wife Patricia (Nikki Amuka-Bird) join the throng, blissfully unaware that every second they spend in sun-kissed paradise takes them closer to oblivion.

Old is a curious meditation on the ageing process, which slips through our fingers like grains of sand, resulting in more furrowed brows and snorts of unintended laughter than gasps of awe and wonder. Bernal and Krieps work incredibly hard to pull sections of their storyline back from the brink of risibility. Shyamalan’s obligatory cameo as the resort’s minibus van driver achieves a low-key naturalism that is somehow denied the rest of the cast or composer Trevor Gureckis’s intrusive, bombastic score.

Find Old in the cinemas

Thriller

Riders Of Justice (15)

Review: Bookended by scenes of festive cheer set to a jaunty rendition of The Little Drummer Boy, Riders Of Justice serves revenge ice cold with a generous drizzle of ghoulish black humour courtesy of writer-director Anders Thomas Jensen. The Danish filmmaker has worked predominately as a scriptwriter, traversing myriad genres with aplomb including his powerhouse collaborations with Susanne Bier on Open Hearts, Brothers and After The Wedding. His latest meditation on masculinity convenes a motley crew of idiosyncratic, eccentric and tormented misfits, who would struggle to exist plausibly on their own in anyone else’s imagination. The diversity of this frequently combative brotherhood warrants a passing on-screen comment – “Sometimes, I think people with problems band together” – before Jensen peels onion-like layers of grief, bullying and sexual abuse from his characters and exposes their most primal fears.

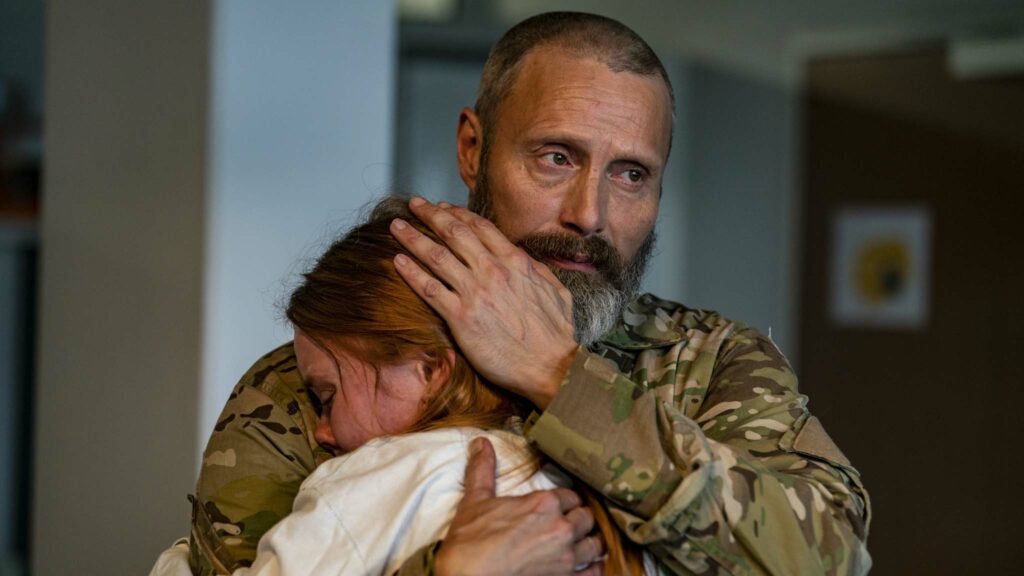

A fiercely committed portrayal of tightly coiled rage and militaristic machismo from Mads Mikkelsen energises every frame and complements some of the script’s more outlandish conceits like a running joke about unconventional therapeutic practices that reap surprisingly sweet rewards. The train crash, which sets desperate blood-soaked events in motion, is orchestrated with economical flair from the perspective of unfortunate passengers, who reach the end of the line just as Jensen’s film is picking up speed.

Shortly before he extends a tour of duty in the Middle East, taciturn soldier Markus (Mikkelsen) learns his wife Emma (Anne Birgitte Lind) has been killed in a railway collision. He sombrely returns to Denmark to comfort teenage daughter Mathilde (Andrea Heick Gadeberg), one of the shell-shocked survivors. Statistician Otto (Nikolaj Lie Kaas), who gave up his seat on the train to Emma and consequently survived, becomes convinced that the accident was the result of foul play. His data indicates it was no coincidence that a prominent biker gang member, due to testify against the Riders Of Justice brotherhood led by Kurt “Tandem” Olesen (Roland Moller), was among the 11 fatalities.

Otto and fellow number cruncher Lennart (Lars Brygmann) approach Kurt with their findings. “I think you have the right to know it wasn’t an accident,” discloses Otto. They recruit hacker pal Emmenthaler (Nicolas Bro) to gather more evidence, setting in motion a bloodthirsty revenge mission that ensnares Mathilde’s boyfriend Sirius (Albert Rudbeck Lindhardt) and a Ukrainian sex worker (Gustav Lindh).

Riders Of Justice steadily builds tension as Markus and his comrades enact their daredevil plan to punish anyone they hold accountable for the crash. Jensen’s off-kilter sense of humour keeps us on our toes but when it comes to tying up loose narrative threads, he surrenders to a heavily armed conventional final showdown. In cinematic punctuation, a fresh bullet wound doubles neatly for a full stop.

Find Riders Of Justice in the cinemas

Romance

The World To Come (15)

Review: The heart desires what it cannot have in director Mona Fastvold’s swooning period romance, adapted for the screen by Ron Hansen and Jim Shepard from one of the short stories in his acclaimed 2017 collection. Handsomely crafted and blessed with sensual lead performances from Katherine Waterston and Vanessa Kirby, The World To Come sustains numerous paper cuts from its source material with a heavy reliance on the voiceover narration of diary entries to convey a female character’s fluctuating emotions. These prosaic musings, which bookmark changing seasons in 1856 upstate New York with jarring frequency, are artful – “My self-education seems the only way to keep my unhappiness from overwhelming me” – but they interrupt the narrative flow and deny actors an opportunity to convey inner turmoil with their eyes and gestures.

Cinema speaks a different and equally rich language to literature but Fastvold’s picture gets tongue-tied in translation. Director of photography Andre Chemetoff complements the omnipresent inner monologue with colour-bleached images of a pastoral idyll at the mercy of Mother Nature. A sequence in a swirling blizzard is particularly striking, contrasting the hushed darkness of an outbuilding where one character seeks shelter with the roaring expanse of white that greets another as they venture into the storm with a rope tied around their waist to tether them to home.

Set on the East Coast frontier, the story pivots initially around hard-working farmer Dyer (Casey Affleck) and wife Abigail (Waterston). It has been a year since diphtheria wrenched four-year-old Nellie from the couple’s loving arms and they never speak about their loss. Dyer and Abigail are desperately lonely in each other’s company, sharing a breakfast of a freshly baked potato in silence before they fulfil duties on the farm then retire to opposite sides of a cold marital bed. When hog farmer Finney (Christopher Abbott) and flame-haired wife Tallie (Kirby) rent a neighbouring property, Abigail finally has someone to talk to.

Sisterhood kindles sparks forbidden passion and Abigail and Tallie embark on an affair that softens the drudgery of their everyday existence. Dyer observes changes in Abigail’s countenance. “I would die without you,” he whispers to his wife as the couple share a rare bedtime embrace. “Then you are safe, because I am here,” she plaintively responds.

The World To Come is a painterly study of female desire that works most effectively when Abigail neglects to take up her diarist’s pen. Stylised dialogue has a pleasing rhythm and lyrical quality. The on-screen electrical charge between Waterston and Kirby is palpable and Fastvold’s direction revels in lingering glances and stolen touches. Wild sexual abandon is reserved for a montage of mournful recollection. By virtue of Abigail’s narration, Abbott’s supposedly abusive spouse is confined to a handful of scenes and feels malnourished in the company of other weather-beaten characters.

Find The World To Come in the cinemas