Horror

Antebellum (15)

Review: Gerard Bush and Christopher Renz’s provocative thriller hinges on a jaw-dropping twist, revealed around the hour mark, that picks at the fresh wounds of the Black Lives Matter movement and revisits horrors endured by generations based on the colour of their skin. Antebellum thrums with audacity but once you recover from the chill down the spine of that narrative sledgehammer blow, which calls to mind one of M Night Shyamalan’s more outlandish exercises in fantasy horror, cool-headed close scrutiny poses more troubling questions that Bush and Renz see fit to answer.

Their outlandish construction threatens to collapse, increasing the weight on lead actress Janelle Monae’s shoulders to deliver two committed performances as women separated by more than 200 years of blood-spattered American history. Echoes of Jordan Peele’s Oscar-winning nightmare Get Out reverberate in a final act that strains credibility, forcefully reminding us of an opening quotation by American writer William Faulkner which sets the wheels in motion: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Bush and Renz set out their stall in emphatic fashion with a bravura unbroken tracking shot through a reformer plantation in Louisiana commandeered by the 9th infantry of the Confederate army of the 13 States. The camera luxuriates uncomfortably on Eden (Janelle Monae) and fellow slave Eli (Tongayi Chirisa) as they await brutal punishment for attempted escape. The General (Eric Lange) lashes Eden with the buckle end of his belt – “I will tame your savage ways!” – and her resistance crumbles in gushing sobs. She returns to cotton fields patrolled on horseback by glowering Captain Jasper (Jack Huston) and his men. Weeks later, soldiers arrive with more terrified slaves including a spirited and outspoken young woman (Kiersey Clemons), who the general’s daughter (Jena Malone) christens Julia.

The new arrival attempts to reignite Eden’s rebellious spirit (“You think being quiet is being strong?”). The trill of a mobile phone jolts us to the new reality of Veronica Henley (Monae again), an author with a doctorate in American constitutional history, who lives in present-day Washington DC with husband Nick (Marque Richardson) and their young daughter Kennedi (London Boyce). A book tour takes Veronica to Louisiana where she enjoys a boozy night out with gal pals Dawn (Gabourey Sidibe) and Sarah (Lily Cowles). Past and present converge with sickening consequences and Veronica heeds her own written words to emerge from the mind-boggling melee.

For better or worse (more the latter), Antebellum inspires feverish debate as directors Bush and Renz remove the dust sheets from their ambitious grand design. Aside from Monae, the cast is short-changed but Sidibe enthusiastically scene-steals, offering welcome comic relief as a relationship guru who knows her worth and loudly celebrates it. She could give the scriptwriters a few lessons in the art of seduction.

Find Antebellum in the cinemas

Action

Chaos Walking (12A)

Review: If innermost thoughts and base desires were exposed as gaseous audio chatter around our heads, we’d probably be driven mad by the unfiltered cacophony. Prejudice, intolerance, jealousy, lust – all shamefully broadcast as unvarnished and discomfiting candour to friends, family and passing strangers. Thinking out loud is commonplace in director Doug Liman’s dystopian sci-fi thriller. Crudely torn from the pages of the first book of a young adult trilogy penned by Patrick Ness, Chaos Walking harnesses slick digital effects to realise a nightmarish world stripped of privacy.

Ness and co-writer Christopher Ford surgically remove nuances and emotional complexities evident on the page of The Knife Of Never Letting Go and opt for bombastic, action-oriented storytelling that neutralises any possibility of an audience engaging brains. Characters’ motivations are rendered in broad, simplistic strokes and a futuristic battle for fractured hearts and minds becomes another blushing pretender to The Hunger Games’ cinematic crown. Daisy Ridley and Tom Holland abandon the Star Wars and Marvel Comics universes to lend their undeniable star wattage to a murky, misguided adventure that crudely stitches together action sequences and forcibly wrings crocodile tears by threatening the life of a cute canine. “Weakness rots from within,” notes the film’s glowering villain. Physician, heal thyself.

Orphaned runt Todd Hewitt (Holland) lives on the mid-23rd century planet of New World in the exclusively male settlement of Prentisstown with adoptive fathers Ben Moore (Demian Bichir) and Cillian Boyd (Kurt Sutter). The women, including Todd’s mother, were killed by the indigenous species, the Spackle, abandoning grief-stricken men to their thoughts, which are audible and visible as a swirling, iridescent cloud-like noise. Mayor David Prentiss (Mads Mikkelsen) has mastered the art of silencing his stream of consciousness, which allows him to exert control over the townsfolk.

Faint flickers of resistance are snuffed out by his hot-headed son David (Nick Jonas) and the righteous indignation of a preacher (David Oyelowo). A spaceship crash-lands close to Prentisstown. The sole survivor, Viola Eade (Ridley), isn’t cursed with the noise and her stoic silence poses a grave threat to the mayor’s iron-fisted rule. “If you want to protect the girl, you have to leave now,” Ben urges Todd, inspiring his ward to go on the run with Violet and pet dog Manchee.

Chaos Walking clearly signals its intentions, as if afflicted by the noise, and propels Todd and Viola on their blood-soaked odyssey without giving us one compelling reason to care about the fugitives. In brief moments when Ridley and Holland can flex dramatic muscles, they elevate the muddled material. Set pieces including a motorcycle chase and river rapids escape are solidly engineered but devoid of tension. Dispel any fanciful thoughts of Chaos Walking sowing the seeds of a franchise. Liman’s picture is creatively barren.

Find Chaos Walking in the cinemas

Action

Godzilla Vs Kong (12A)

Review: Billed as the ultimate showdown between behemoth brawlers from Godzilla: King Of The Monsters and Kong: Skull Island, director Adam Wingard’s overblown monster-mashing smackdown is a ridiculously one-sided affair. Logic, not a quality cherished by screenwriters Eric Pearson and Max Borenstein, dictates the outcome when a reptilian contender with atomic breath that cuts through metal like a hot knife through butter rumbles with a chest-beating rival armed with banana breath. Godzilla Vs Kong shamelessly milks affection for the underdog ape with an opening croon of Bobby Vinton’s Over The Mountain, Across The Sea as the hulking primate wakes dreamily on his island idyll, lazily scratches his hirsute haunches and enjoys a bracing shower in a waterfall.

Wingard’s testosterone-fuelled picture is just as one-sided. Bombastic action sequences, choreographed in luscious slow-motion, bludgeon character development and plausible plotting into a coma without resistance. The titular death match is conducted as two eye-popping bouts on sea and land roughly an hour apart, one of which cheerfully asks us to believe that a US Navy aircraft carrier could support the combined weight of the title fighters rampaging on its deck in the Tasman Sea.

“There can’t be two alpha titans,” prophesises anthropologist Dr Ilene Andrews (Rebecca Hall). It takes almost two hours of fist-pummelling fury to prove her wrong. Dr Andrews works for secret scientific organisation Monarch on Skull Island, safely containing Kong inside a hi-tech dome where her deaf ward Jia (Kayle Hottle) secretly communicates with the prize specimen using sign language. Former Monarch scientist Nathan Lind (Alexander Skarsgard), labelled “a sci-fi quack trading in fringe physics”, implores Ilene to let him transport Kong to Antarctica to prove his crackpot theory about a hollow earth ecosystem at our planet’s core.

The mission is bank-rolled by Walter Simmons (Demian Bichir), chief executive of Apex Cybernetics, who believes this hidden world could unlock a power source to protect mankind from future titan threats. Needless to say, his motives are not as altruistic as the ramshackle script begs us to believe. Meanwhile in a superfluous subplot, spunky teenager Madison Russell (Millie Bobby Brown), daughter of Monarch’s deputy director of special projects (Kyle Chandler), unravels the Apex conspiracy with a wise-cracking classmate (Julian Dennison) and conspiracy theorist podcaster (Brian Tyree Henry).

Godzilla Vs Kong has just one emotional string to its bow, the bond between cherubic Jia and the ape, and scriptwriters Pearson and Borenstein pluck it frantically between impressive yet exhausting set pieces. The introduction of a third challenger to the ring for a tag team finale among Hong Kong’s tumbling skyscrapers cranks up the wanton devastation on an epic scale. The wall of sound of Thomas Holkenborg’s synth score launches a sustained assault on the ears to match the visual blitzkrieg.

Find Godzilla Vs Kong in the cinemas

Drama

The Mauritanian (15)

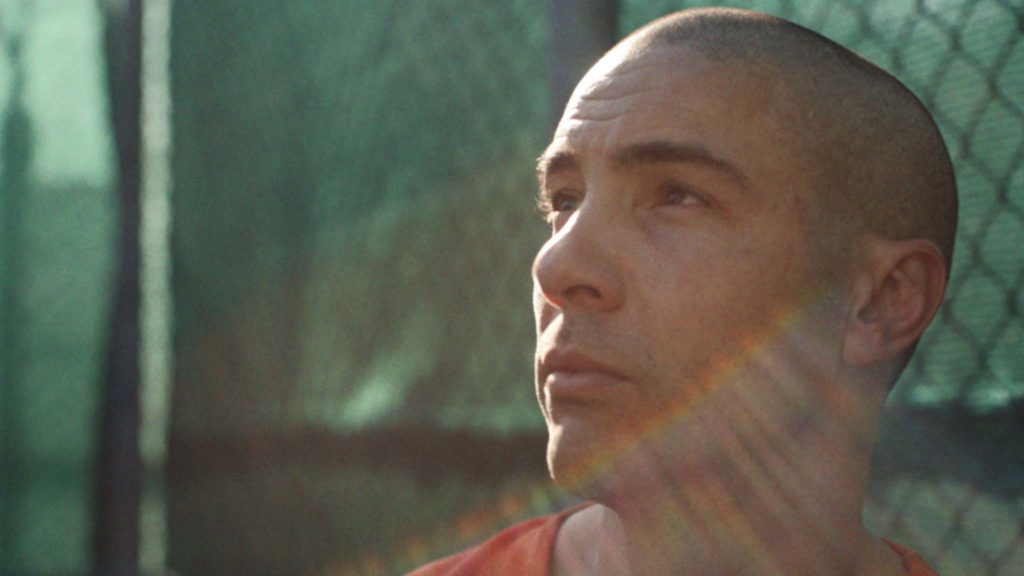

Review: Compassion, humanity and basic civil rights become collateral damage of the so-called war on terror in Glasgow-born director Kevin Macdonald’s legal drama. Based on Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s harrowing memoir Guantanamo Diary, written during detention on Cuban soil, The Mauritanian coolly details Slahi’s horrifying ordeal, which saw him held without charge for 14 years and subjected to sleep deprivation and torture. Scriptwriters MB Traven, Rory Haines and Sohrab Noshirvani oscillate between Slahi and the opposing legal eagles, played with fiery determination by Jodie Foster and restraint by Benedict Cumberbatch, who end up on the same side when they separately discover the methods used to extract an incriminating statement.

Those scenes of violence and intimidation, including a mock execution at sea shot from the point of view of the hooded prisoner, are grist to Macdonald’s cinematic mill as he celebrates the enduring power of the human spirit. French actor Tahar Rahim brings a quiet determination and warmth to Slahi, who opens his evidence to the District Court Of Columbia without any apparent bitterness: “I do not hold a grudge against those who abused me.”

In Macdonald’s film, we first meet Mohamedou in November 2001, carefree among revellers at a traditional Mauritanian wedding. The head of the northwest African republic’s intelligence service arrives to spirit him away for questioning about his cousin and brother-in-law Mahfouz Ould al-Walid, whose ties to al-Qaeda and Osama Bin Laden are red flags for the Americans. Mohamedou leaves the festivities, cheerfully telling his mother: “Save me some cake.” They never lock eyes again. Three years later, German newspaper Der Spiegel publishes an article claiming Mohamedou is being held at Guantanamo Bay on suspicion of being one of the organisers of the September 11 attacks.

French lawyer Emmanuel Coste (Denis Menochet) brings the case to the attention of no-nonsense criminal defence lawyer Nancy Hollander (Foster). She arranges access to Mohamedou accompanied by associate Teri Duncan (Shailene Woodley). Meanwhile, Colonel Bill Seidel (Corey Johnson) approaches Lieutenant Colonel Stuart Couch (Cumberbatch) to lead the death penalty case against Mohamedou. The Mauritanian is accused of recruiting Marwan Al-Shehhi, hijacker pilot of United Airlines flight 175. Couch’s friend Bruce Taylor was a passenger and the military prosecutor swears justice for the fallen.

Prefaced simply by “This is a true story”, The Mauritanian ticks off cinematic tropes such as lawyers doggedly sifting through evidence boxes and an affirmation that the guilty have a right to robust legal counsel. It is captivating albeit conventional storytelling, enlivened by the performances, particularly Foster’s rabble rouser. One minute of real footage of Mohamedou returning to Mauritania packs the biggest emotional punch, throwing into sharp relief the clinical, clean cut approach of Macdonald’s film to its inspirational subject.

Find The Mauritanian in the cinemas

Drama

Minari (12A)

Review: Writer-director Lee Isaac Chung plunders memories of his childhood in the shadow of the Ozark Mountains in an autobiographical love letter to family ties and intergenerational conflict. Glimpsed through the eyes of a Korean American couple, who relocate their brood to 1980s Arkansas, Minari charms and delights without flashiness, relying on naturalistic performances from a powerhouse ensemble cast and the untouched beauty of the Bible Belt to cast a heady spell. Taking its title from the luscious water cress which flourishes in Korea, Chung’s beautifully calibrated character study balances moments of regret with earthy humour including an impish boy serving an elderly relative a fragrant brew they won’t forget.

Eight-year-old Alan S Kim’s performance as the mischievous tyke is a source of endless delight and is a glowing testament to writer-director Chung’s ability to tease out authenticity from the youngest member of cast without trading too heavily on winsomeness. Supporting Actress Oscar nominee Youn Yuh-jung is a lip-smacking delight as the potty-mouthed grandmother with scant regard for social niceties, who shatters the peace with the cool disregard of a wrecking ball. In the rubble, Minari unearths moments of life-affirming joy and despair from a gifted filmmaker’s heart.

Korean immigrant Jacob Yi (Steven Yeun) transplants his wife Monica (Yeri Han) and their two children Anne (Noel Cho) and David (Kim) from California to Arkansas. “This is the best dirt in America,” coos David, allowing the earth to tumble through his fingers as he admires 50 acres of untouched wilderness. Monica is unimpressed: their new home is an hour from the nearest hospital, where David is undergoing treatment for a heart condition. “If this is the start you wanted, maybe there’s no chance for us,” she rues.

The despondent wife invites her cantankerous mother (Yuh-jung) to travel from South Korea to the family plot. The elderly matriarch arrives bearing chilli powder and anchovies but no sympathy for her little nephew’s night-time bed-wetting (“Ding dong broken!”) or her daughter’s softly-softly approach to parenting. Meanwhile, David enlists God-fearing neighbour and Korean War veteran Paul (Will Patton) to grow fruit and vegetables to sell in nearby Dallas.

Minari balances sweetness and spice like expertly made kimchi to a recipe of heartfelt emotion in Chung’s simple yet effective script. Yeun’s moving embodiment of a proud father desperate to provide for his children (“They need to see me succeed at something for once”) gels magnificently with Han’s increasingly disillusioned wife. Misfortune and tests of religious faith punctuate a bittersweet family album, which quietly champions the pursuit of one American dream that doesn’t mean sacrificing cherished traditions. Harmony can blossom in the divide between competing cultures and Chung skilfully harvests an entertaining and enthralling crop.

Find Minari in the cinemas