Thriller

The Critic (15)

Review: Sir Ian McKellen makes merry as an embittered theatre reviewer, notorious for bile-slathered diatribes and occasionally cruel quips about an actor’s appearance, in director Anand Tucker’s efficient 1930s-set thriller. Adapted by Patrick Marber from Anthony Quinn’s 2015 novel Curtain Call, The Critic delights in the devastation wrought by McKellen’s waspish wordsmith as he bulldozes through other people’s lives and shows a similar disregard for his personal safety as a gay man cruising for sex in parks when homosexuality was illegal.

An ill-fated blackmail plot provides a robust dramatic structure and Tucker tightens screws on doomed and largely unlikeable characters as their fortunes unravel through lust, arrogance and greed. McKellen sinks his pearly whites into each scathing putdown and he catalyses delightful cat-and-mouse screen chemistry with Gemma Arterton’s struggling actress, who yearns for words of approval and is expertly manipulated into betraying her moral compass. Powerhouse supporting female cast including Lesley Manville and Romola Garai are underused.

If the title character was penning an assessment of Tucker’s picture, I suspect he would decree it fails to wholeheartedly deliver on the promise of high-calibre talent behind and in front of the camera. To directly quote McKellen’s egotistical arbiter of cultural taste: “Only the greats are remembered.”

In 1934 London, Jimmy Erskine (McKellen) is the universally feared and revered drama critic of The London Chronicle, perpetually flanked by his loyal secretary, Tom Tunner (Alfred Enoch). Erskine’s glowing praise or withering putdowns have the power to elevate theatre makers and performers overnight or shutter a play before the dust has settled from the fall of an opening night curtain. He is an impassioned torch bearer for the art form (“Theatre matters more than politics!”) and bristles when an editor suggests an amendment to one particularly florid word. “I doubt our readers can read,” Erskine pithily retorts.

When David Brooke (Mark Strong) inherits ownership of The London Chronicle from his late father and makes swingeing cuts, Erskine and the old guard including opera critic Hugh Morris (Ron Cook) fear their days are numbered. In retaliation, Erskine hatches a diabolical plan to ruthlessly exploit Brooke’s obsession with actress Nina Land (Gemma Arterton), unaware that the stage starlet is having an illicit affair with Brooke’s brother-in-law (Ben Barnes).

The Critic elegantly outlines its cruel intentions in the opening hour and calmly delivers dire and predictable outcomes for almost everyone ensnared in Erskine’s web. Pacing is steady, to the film’s detriment, in an inevitably tragic final act when heightened stakes should quicken pulses. McKellen is imperious, meeting potential setbacks with pursed lips and a lexicon of bile. He will be fondly remembered when the film around him quietly fades to black.

Find The Critic in the cinemas

Drama

Lee (15)

Review: Born and raised in Poughkeepsie, New York, Elizabeth “Lee” Miller was one of the defining photographers of the Second World War but her devastating images of the conflict were largely lost in time until after her death from cancer in 1977. The dramatically uneven feature directorial debut of award-winning American cinematographer Ellen Kuras addresses the oversight, focusing on a 10-year period when Miller traded life as a fashion model to become war correspondent for Vogue magazine. “I’d rather take a picture than be one,” explains Miller, portrayed with gusto over almost 40 years by Kate Winslet.

The Oscar winner is formidable, most powerfully when Miller walks through a concentration camp and the anguish etched into her face conveys the stomach-churning horror of everything she sees (and Kuras conceals off screen). Compelling background detail, like Miller honing her craft with the artist Man Ray in Paris, is omitted even as expository dialogue, and the script’s episodic structure often feels like a whistlestop tour of memorable photographs from the archive. Andy Samberg enjoys a dramatic role as the photographer who teamed up with Miller in the heart of darkness and Andrea Riseborough savours fleeting moments as the influential magazine editor who championed Miller at a time when a woman’s place certainly wasn’t on the front line.

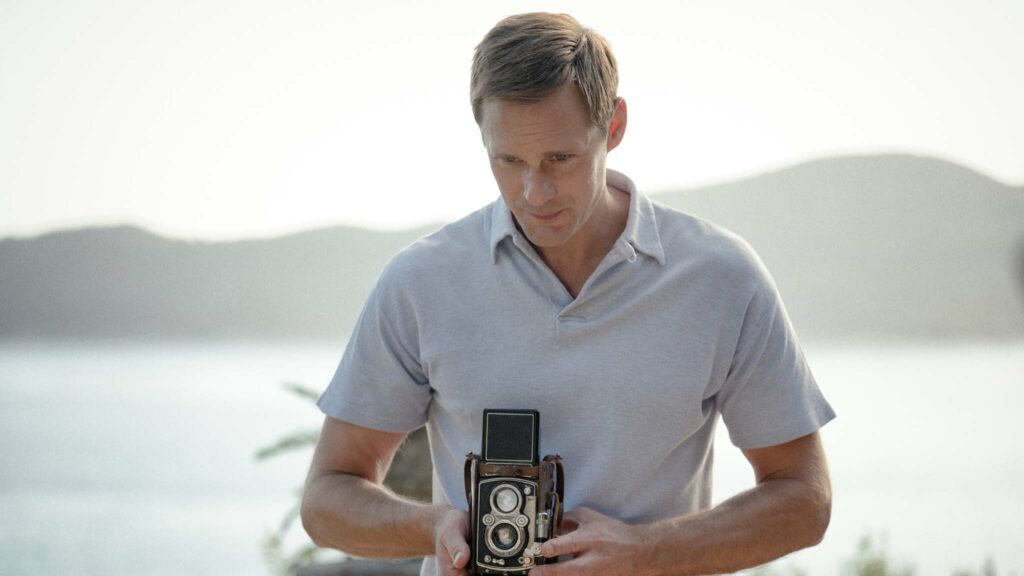

In 1977, 70-year-old American photographer Lee Miller (Winslet) sits across from an interviewer (Josh O’Connor) in her East Sussex home to reminisce about her extraordinary career. She recalls idyllic days before Hitler’s rise to power with friends Solange d’Ayen (Marion Cotillard), Paul Eluard (Vincent Colombe) and wife Nusch (Noemie Merlant). An erotically-charged courtship with painter and poet Roland Penrose (Alexander Skarsgard), who would become her husband in 1947, is interrupted by Hitler’s ascent.

With the support of British Vogue’s editor Audrey Withers (Riseborough), Lee heads to the front line to document the conflict but she meets fierce resistance from military command. Colonel Spencer (James Murray) eventually relents and Lee glimpses the Second World War through a lens in the company of Life magazine’s correspondent David Scherman (Samberg), including sickening images from inside Dachau. “Even when I wanted to look away, I knew I couldn’t,” she sombrely intones.

Adapted from Antony Penrose’s biography of his mother, Lee is a staunchly conventional biopic that scratches the surface of Miller’s contribution to wartime photojournalism. Winslet is fearless, shedding inhibitions to capture the exuberance and steely resolve of a trailblazer, who by her own admission was always “the last to leave the party”. Kuras’s party is a thoughtful celebration of Miller that lacks those finer, messier details that would help us to connect on a deeper and profound level beyond glowing admiration.

Find Lee in the cinemas

Horror

Speak No Evil (15)

Review: Beware the kindness of strangers. It’s a harsh lesson that the overly polite characters in writer-director James Watkins’ English language remake of a disturbing 2022 Danish horror absorb and apply far too late to avoid paying a hefty toll in blood, tears and shattered bones. Relocated from rural Netherlands to a remote area of the West Country, the second iteration of Speak No Evil is markedly less dark and twisted than its relentlessly creepy predecessor.

The jaw-dropping and unflinchingly brutal denouement of director Christian Tafdrup’s version, which sent a shiver of pure terror down the spine, has been jettisoned for a more conventional and palatable showdown between good and evil. If you have supped from the spiked punch bowl of the original, Watkins’ picture will taste mellow by comparison.

His script appropriates lines of dialogue and the barbed commentary about social etiquette and apathy but makes some questionable detours such as temporarily ignoring one freshly sustained injury, which would require medical attention and seriously hamper a character’s motor skills. James McAvoy channels the simmering menace of his kidnapper with dissociative identity disorder in Split as the remake’s passive-aggressive chief antagonist and he embraces snarling, full-blooded lunacy when Watkins’ film finally bares its teeth. Speak No Evil’s bark is far worse than its bite, more’s the pity.

American couple Ben and Louise Dalton (Scoot McNairy, Mackenzie Davis) and their anxiety-crippled daughter Agnes (Alix West Lefler) are recent transplants to rain-lashed London, who seek sun and solace on holiday in Europe. The family encounters gregarious English doctor Patrick Feld (McAvoy), his wife Ciara (Aisling Franciosi) and their young son Ant (Dan Hough). The boy cannot speak because of a rare condition called congenital aglossia, which means he was born without a tongue.

Patrick curries favour with the Daltons by flouting social niceties to ward off other holidaymakers from sitting with them for lunch. The Felds subsequently invite the Daltons to visit them on their rambling country estate. Louise is reluctant to spend time with people they barely know but she banishes her concerns for Ben so they can continue to heal a rift in their marriage. The Daltons become concerned about their hosts’ unsettling behaviour, especially Patrick’s abusive treatment of Ant, and Louise privately seethes at Ben’s reluctance to cause a scene.

Speak No Evil is a solidly entertaining psychological thriller that doesn’t push nihilistic boundaries to the same degree as its Scandinavian counterpart. Action sequences are confidently executed and a totem of childhood innocence – a stuffed rabbit – repeatedly coaxes protagonists into the slavering jaws of mortal danger. One character quotes a French proverb about not letting the quest for perfection stand in the way of achieving a good result. Duly noted. Watkins’ film is good.

Find Speak No Evil in the cinemas