Drama

All Of Us Strangers (15)

Review: Being human is messy. Never more so when our most deeply rooted fear, the death of someone we love, forever alters the ebb and flow of daily life and forces us to confront our fragile mortality in a haze of grief, anger and regret. Based on the novel Strangers by Taichi Yamada, writer-director Andrew Haigh’s achingly beautiful ghost story imagines that maelstrom of conflicting emotions when a 45-year-old man magically reconnects with his late parents, who died in a car crash just before he was 12. Benevolent spectres are frozen in time in 1987 and the central character reverts to a boyish trepidation in their presence, nervously navigating the subject of his sexuality when their frame of reference is a groundswell of bigotry and intolerance in response to the Aids/HIV crisis under Margaret Thatcher’s government.

Andrew Scott is sensational as a loner, who begins to dismantle seemingly unscalable emotional barricades following that devastating loss in adolescence. Haigh’s exquisite screenwriting shines in heartbreaking scenes with phantasmagorical parents, played with tenderness by Jamie Bell and Claire Foy, like when the father belatedly apologises for not comforting his boy during a period of bullying at school: “I’m sorry I never came into your room when I heard you crying.” On-screen chemistry between Scott and Paul Mescal is molten and Haigh choreographs their sex scenes with artful sensitivity.

Fortysomething screenwriter Adam (Scott) lives alone on an upper floor of a recently constructed London apartment building, wrestling with a creative block as he attempts to channel childhood memories into words on his laptop screen. His unedifying seclusion of half-eaten takeaways and late-night television is interrupted by a knock at the door.

Harry (Mescal), who lives on the sixth floor and is desperate for companionship, sways drunkenly in the corridor. “We don’t have to do anything if I’m not your type,” he smiles, hoping to be let in. Adam initially rebuffs Harry but the two men subsequently spark a tender romance which coincides with the screenwriter visiting his childhood home in Sanderstead, south of Croydon. Miraculously, Adam discovers the ghosts of his parents (Bell, Foy) linger at the property.

All Of Us Strangers is essentially a four-hander between Scott, Mescal, Bell and Foy and each member of cast is wondrous. I was almost the same age as Adam in 1987 so a heady scent of nostalgia pervades every frame, crescendo-ing with the Pet Shop Boys’ version of Always On My Mind as the reunited family decorates a Christmas tree. It may be foolish, in January, to anoint Haigh’s haunting picture my favourite film of 2024 but it is hard to imagine another feature moving me so profoundly over the next 12 months. I look forward to be proven wrong.

Find All Of Us Strangers in the cinemas

Horror

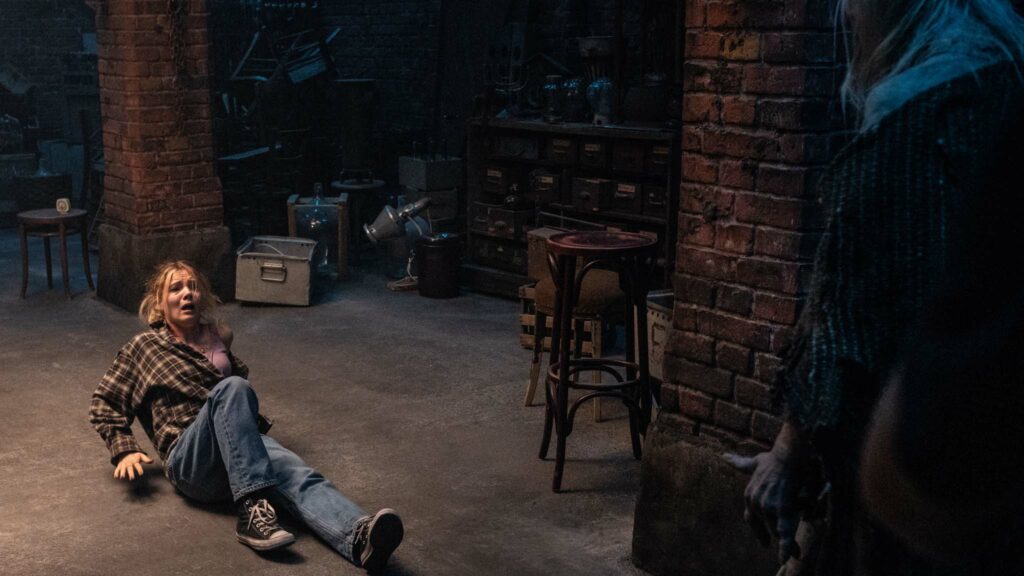

Baghead (15)

Review: Shivers of staccato strings herald impending doom in Baghead, a supernatural horror expanded by director Alberto Corredor from his 2017 short film about a witch living in the storage room of a pub, who reconnects the grief-stricken with the dearly departed… for a price. Screenwriters Christina Pamies and Bryce McGuire appropriate Lorcan Reilly’s original premise for a menacing prologue, which strongly counsels one anguished relative against engaging the crone’s services. “Take your grief elsewhere. You’ll find no peace here,” growls her accursed guardian. Predictably, sage words fall on deaf ears and we don’t have to wait too long before the bloodcurdling screams begin.

It takes considerably longer for Corredor to reveal what lurks beneath the hessian sack worn by Baghead to mask her hideousness, realised with slick digital effects. The script creaks and groans almost as loudly as the centuries-old pub where the carnage is focused, gradually distilling a convoluted mythology mired in secret brotherhoods and generational sin with sporadic jump scares. Baghead calls last orders on our emotional engagement with characters in peril by starving everyone, particularly the beleaguered heroine played by Freya Allan, of relatable and full back stories. We have little sympathy for the almost-dead as potential victims ignore the most basic rule of horror film survival: don’t wander off alone in the dark.

Struggling art student Iris Lark (Allan) is evicted from her flat shortly before she receives a telephone call from Berlin, disclosing the death of her estranged father Owen (Peter Mullan). Iris grew up with feisty best friend Katie (Ruby Barker) and has no memories of Owen but she agrees to travel to Germany to formally identify the body. During the trip, Owen’s solicitor (Ned Dennehy) reveals that Iris has inherited a rundown tavern, The Queen’s Head, which comes with “a special tenant” in the basement: a gnarled creature named Baghead (Anne Muller). The shapeshifting hag has the power to connect the living with the dead by swallowing an object belonging to the deceased.

However, there are dire consequences for using the crone’s services, especially if you exceed a strict two-minute time limit for each otherworldly conversation. Grief-stricken widower Neil (Jeremy Irvine) approaches Iris with a cash-filled envelope so he might speak to his late wife Sarah (Svenja Jung) through Baghead. “Money’s no object. I just want the chance to say goodbye,” he pleads. Desperate to resuscitate her finances, Iris accepts the money and naively opens herself to malevolent corruption.

Baghead traipses lightly on genre ground already haunted by instalments of The Conjuring universe and The Curse Of La Llorona. The titular terror has a much fuller personal history than any of her undernourished victims and by the time the end credits roll, the mounting body count is a blessed relief.

Find Baghead in the cinemas

Musical

The Color Purple (12A)

Review: Structured as a series of letters, Alice Walker’s 1982 novel The Color Purple won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction and was subsequently adapted into an Oscar-nominated film directed by Steven Spielberg. Twenty years later, a musical stage play of The Color Purple with a book by Marsha Norman and music and lyrics courtesy of Brenda Russell, Allee Willis and Stephen Bray enchanted Broadway. I was extremely fortunate to see the Tony Award-winning 2015 revival featuring earth-shattering performances from Cynthia Erivo as Celie and Danielle Brooks as strong-willed Sofia.

Brooks reprises her role in director Blitz Bazawule’s handsome big screen adaptation and almost steals the film with a commanding rendition of the fiery self-empowerment anthem Hell No. She captures lightning in a bottle for a second time in collaboration with choreographer Fatima Robinson and costume designer Francine Jamison-Tanchuck. Co-star Taraji P Henson also seizes her moment in the spotlight with a juke joint performance of Push Da Button wearing an alluring red beaded dress and feather headpiece.

American Idol winner Fantasia Barrino tugs heartstrings as Celie, a survivor of domestic and sexual abuse in early 20th-century rural Georgia determined to find her place in a cruel world. Her heroine’s standout solo, the defiant I’m Here, feels oddly underpowered on screen. She winds up for a mighty emotional wallop but only lands a glancing blow. Thankfully, a poignant finale packs the missing punch.

Teenager Celie (Phylicia Pearl Mpasi) suffers horribly at the hands of her abusive father Alfonso (Deon Cole) until she is married off against her will to local farmer Mister (Colman Domingo), who expects her to take care of his three children. Celie’s spirited sister Nettie (Halle Bailey) refuses to submit to Mister and she leaves Georgia but promises to write every day. Years pass and Celie (now played by Barrino) has been worn down to quiet subservience until Mister’s mistress, sultry jazz singer Shug Avery (Henson), sashays into town and lights a fire in the broken wife.

Mister’s son Harpo (Corey Hawkins) also meets his match in Sofia (Brooks), who walks out on him when he raises a hand to her. Surrounded by powerful women, Celie marshals the confidence to challenge Mister in front of his father (Louis Gossett Jr) and seize control of her destiny.

The Color Purple honours themes of resilience, regret and defiance in Walker’s book, punctuated by large-scale musical numbers that benefit from the pacing created by editor Jon Poll, who previously worked on The Greatest Showman. Cinematographer Dan Laustsen, who has repeatedly collaborated with Guillermo del Toro, intensifies the colour palette and camera movements to differentiate these showstoppers from spoken sections lit by natural light. The sun must eventually rise on Celie and her sisterhood.

Find The Color Purple in the cinemas

Thriller

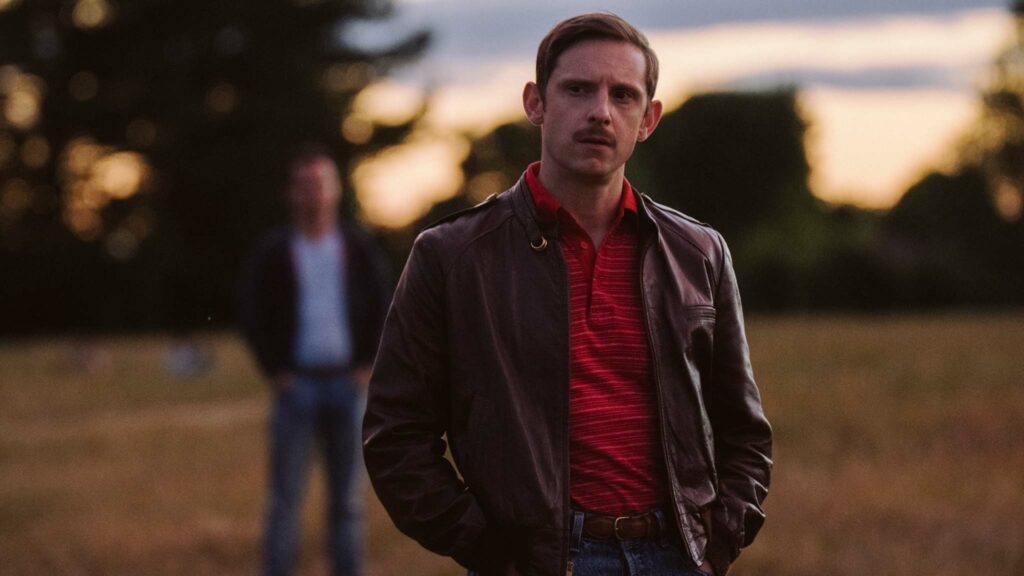

Jackdaw (15)

Review: It’s grim up north. The pulsating 1990s track of the same title by The Justified Ancients of Mu Mu aka The KLF is a fitting soundtrack choice for an assured feature film debut of County Durham-born writer-director Jamie Childs. Shot on location in the Tees Valley area, Jackdaw is a propulsive crime thriller which unfolds over the course of one turbulent night to the relentless electronic beats of The Prodigy, Aphex Twin and Robin S. Childs and cinematographer William Baldy showcase the region’s arresting landscapes in confidently staged set pieces including an open water chase in minus 12 degrees in the North Sea and a bruising fistfight between the eponymous hero (whose name is conveniently tattooed on the back of his neck) and knife-wielding henchmen.

Visually, the film impresses and leading man Oliver Jackson-Cohen provides plentiful evidence with his on-screen acrobatics that he could comfortably inherit James Bond’s licence to kill. Childs’s script isn’t quite so muscular or robust, barely sustaining a lean 97-minute running time with a linear plot, lukewarm romance and generic lines of dialogue that sound hollow tumbling from actors’ lips (“Be careful Jack. The road ahead is paved with good intentions”).

Former motocross champion and army veteran Jack Dawson (Jackson-Cohen), known affectionately as Jackdaw, returns home unannounced to Hartlepool to avoid attracting the attention of local hard man Armstrong (Rory McCann). Jack is resolved to care for younger brother, Simon (Leon Harrop), following the recent death of their mother. Living quietly in a port town filled with bad memories requires sacrifice and Jack reluctantly accepts a job from criminal Silas (Joe Blakemore) to complete an open water pick-up of a mysterious package. The consignment is attached to a buoy near a wind farm and Jack barely escapes by kayak from two gun-toting men on jet skis.

Heading to the drop-off point on two wheels, Jack discovers he has been double-crossed and when he returns home, Simon is missing and the letter S is etched into the kitchen table. Jack heads into the night to rescue Simon. The suicide mission necessitates assistance from a well-connected local gym owner (Vivienne Acheampong) and old flame Bo (Jenna Coleman). En route, Jack acquires a wisecracking sidekick, a raver named Craig (Thomas Turgoose) who cheekily claims he doesn’t fancy his chances “with a guy with a crowbar dressed like a low budget Power Ranger”.

Jackdaw confirms it is possible to choreograph a high-octane action thriller with a quintessentially British tang. Jackson-Cohen commands attention, especially in quieter scenes, and Turgoose provides welcome comic relief to dissipate tension. Budgetary constraints are only evident in a police raid sequence but Childs generates pleasing bursts of kinetic energy from his simple premise. In those nervy-jangling interludes, his Jackdaw takes flight.

Find Jackdaw in the cinemas