Drama

Living (12A)

Review: In 2008, when my mother lost a battle of attrition against cancer like so many beautiful, fierce warriors before her, I resolved to deeply cherish my father (I tell him that I love him every day) and the relationships that nourish me. I feel grateful beyond words that my mother and I parted ways without secrets or regrets, and as her final act of unconditional love, she encouraged me to seek clarity in a sea of grief and despair that I feared would swallow me whole. Memories of that time are my constant companion and they resurfaced during director Oliver Hermanus’s exquisite English-language remake of Akira Kurosawa’s 1952 drama Ikiru about a terminally ill man who acknowledges the emptiness of his existence just before it is cruelly snatched from him.

Relocated from post-war Japan to London by Nobel and Booker Prize-winning novelist and screenwriter Kazuo Ishiguro (The Remains Of The Day), Living wreaks emotional devastation in the lingering silences between characters who have kept calm and carried on since the Second World War. Those moments when the right words do not materialise – between a dying father and his clueless son, between sharp-suited civil servants at the mercy of bureaucratic red tape – are heartbreaking, and Hermanus allows us the time and space to feel each desolating blow.

A career-best central performance from Bill Nighy, who will be a formidable contender for Best Actor at next year’s Oscars, galvanises every elegantly crafted scene. He delivers a mesmerising masterclass in painfully quiet servitude tinged with regret that dials back the comic flamboyance we have come to expect from the gregarious star of Love Actually. Touching interludes with co-star Aimee Lou Wood’s work colleague, one of the few people to know his medical diagnosis and witness a renewed resolve in the shadow of death, glister like perfectly polished gemstones.

Widowed bureaucrat Mr Williams (Nighy) diligently shuffles papers at County Hall, overseeing public works alongside Mr Middleton (Adrian Rawlins), Mr Rusbridger (Hubert Burton), Mr Hart (Oliver Chris), Ms Harris (Wood) and new arrival Mr Wakeling (Alex Sharp). A medical check-up reveals a diagnosis of terminal stomach cancer and once Mr Williams finally whispers the dreaded words aloud (“The doctor has given me six months… eight or nine at a stretch”), he seeks peace by personally championing plans for a children’s playground.

Living is a magnificent meditation on mortality that savours every second of the 102-minute running time. Nighy delicately plucks our heartstrings, whether he is stumbling through a booze-sodden jaunt with a sympathetic stranger (Tom Burke) or weathering awkward exchanges with his unsuspecting son (Barney Fishwick) and daughter-in-law (Patsy Ferran). Cinema is most powerful when reality is refracted through a lens. Hermanus’s picture refuses to avert its sympathetic gaze. Life is a series of discomfiting and joyful first takes until some greater power calls “cut”.

Find Living in the cinemas

Thriller

Watcher (15)

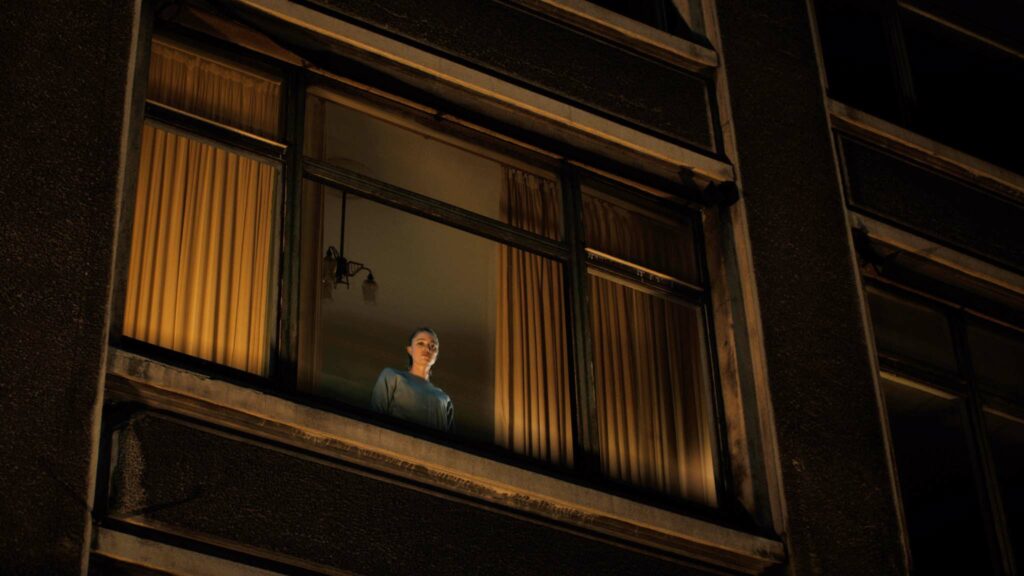

Review: Cinema is an act of voyeurism – an open invitation to spy on the day-to-day activities and private moments of other people from the comfort of a darkened theatre. Sometimes those lives in motion are real, captured raw and spontaneously by documentary filmmakers. More often, they are wildly imagined by screenwriters or adapted from rich source material. Writer-director Chloe Okuno’s unsettling horror draws breath from the most relatable type of voyeurism – furtive surveillance of neighbours – and steadily cranks up dread by imagining the consequences if one of those nearby residents was a serial killer on the hunt for their next victim.

Based on an original screenplay penned by Zack Ford, Watcher revels in suggestion and paranoia, pushing an increasingly unhinged heroine to the brink of a nervous breakdown as she feverishly questions her intuition in a foreign country where she barely speaks the language. Lead actress Maika Monroe confidently rides that emotional rollercoaster with whitened knuckles. She has excellent form in the genre, narrowly escaping the clutches of a sexually transmitted spectre in It Follows.

In Watcher, Monroe brilliantly evokes the spirally disorientation of an outsider starved of sleep and rational thought, who fears no one will hear her cries if her darkest fears are realised and she is being stalked by a murderous predator. Cinematographer Benjamin Kirk Nielsen takes notes from Stanley Kubrick and Roman Polanski to mine terror from wide, open spaces. Nowhere is safe.

Actress Julia (Monroe) and husband Francis (Karl Glusman) relocate from New York to Romania, his mother’s homeland, for a promotion to the Bucharest office of his marketing company. They move into a spacious apartment with large windows overlooking a courtyard and a similar block of flats. Francis spends long hours at work. Thankfully, next-door neighbour Irina (Madalina Anea) speaks English and is sensitive to Julia’s feelings of isolation.

Alone in the apartment, Julia notices a man across the street staring back at her. She learns the capital is in the grip of a serial killer nicknamed The Spider and Julia fixates on the possibility that the neighbour opposite, Daniel Weber (Burn Gorman), might be the perpetrator. Following an unsettling encounter with Daniel at a local supermarket, Julia and Francis review CCTV footage. “He’s staring at me!” she professes, referencing a frozen image on the screen. “Or he’s staring at the woman that’s staring at him,” calmly rationalises Francis.

Watcher is a stylish and clinical study of psychological disintegration, tethered to Julia’s powerlessness because no crime has been committed. Monroe hits every emotional beat as her character is dragged repeatedly through the wringer and Gorman perfects a chillingly silent stare that could be social awkwardness or something sinister. Writer-director Okuno’s vice-like grip loosens in the final 10 minutes but the hard work has already been accomplished.

Find Watcher in the cinemas