Drama

H Is For Hawk (12A)

Review: A grief-stricken university fellow ruffles feathers when she buys a goshawk to cope with the death of a parent in director Philippa Lowthorpe’s touching drama adapted from Helen Macdonald’s memoir. Buoyed by a tremendous lead performance from Claire Foy, H Is For Hawk is an intimate and melancholic study of loss, both of a soulmate and oneself.

In 2007 Cambridge, Jesus College academic Helen Macdonald (Claire Foy) is devastated when her father Alisdair (Brendan Gleeson), a celebrated press photographer who nurtured her love of natural science, dies suddenly from a heart attack. She returns home to assist with funeral arrangements but is unable to process her emotions alongside her mother Jane (Lindsay Duncan) and brother James (Josh Dylan). Cast adrift in a sea of grief, Helen reminisces about chasing goshawks during her bucolic childhood and she fixates on the idea of training a wild bird to hunt and fly.

Her father’s good friend Stuart (Sam Spruell), who has experience with birds of prey, urges Helen to reconsider acquiring a goshawk: “They’re a handful.” She ignores his sage advice and heads to windswept Stranraer with good friend Christina (Denise Gough) to buy a goshawk from a breeder, which she subsequently christens Mabel. Helen slowly bonds with the creature back in Cambridge, overidentifying with the bird and ignoring a heartfelt plea from her mother to remain grounded in the land of the living: “Just don’t get lost!” The academic devotes every waking moment to Mabel, retreats from family and friends, neglects her university students and completely forgets about her seminar entitled Icons Of Extinction. Rather than salve her grief, Helen risks being consumed by it.

Adapted for the screen by Emma Donoghue and director Lowthorpe, H Is For Hawk glides serenely between elegantly staged scenes of anguish, building slowly to the acknowledgement of a mental health diagnosis. Hunting sequences of a goshawk wheeling and swooping in pursuit of prey are thrillingly captured by wildlife cinematographer Mark Payne-Gill. Foy learned falconry for the role and in remarkable scenes, the camera lingers on the actor as she teaches a goshawk to trust her and tear strips of flesh from a gloved hand.

The bird flaps wildly, twisting in the air to escape its tether, but Foy sits calmly with her arm outstretched until her feathered companion submits. She wrenches out her character’s fractured heart in close-up and sparks delightful on-screen rapport with Gleeson in flashback and mournfully imagined reconciliations post-mortem. A repeated quote by 14th-century mystic Julian of Norwich from Revelations Of Divine Love proves apt for both Helen’s on-screen journey towards healing and Lowthorpe’s poetic picture. “All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well.”

Find H Is For Hawk in the cinemas

Romance

The History Of Sound (15)

Review: Writer-director Oliver Hermanus strikes an emotional chord with his elegant romance expanded from Ben Shattuck’s original short story but the notes he plays are soft and polite, even with stirring performances from Paul Mescal and Josh O’Connor as secret lovers, who stoke desire before and after the First World War inflicts deep psychological scars on a generation of idealistic, young men.

In 1917 New England, unassuming Conservatory of Music student Lionel Worthing (Mescal) meets David White (O’Connor) tinkling the ivories in a bar. There is an instant connection between two men with a mutual interest in the rich history of folk music. They spark a passionate affair, conducted breathlessly behind closed doors, which is cut short when America enters the conflict. David is drafted but Lionel’s poor eyesight exempts him from service. “Don’t die,” implores Lionel staring into his lover’s glassy eyes.

Years later, Lionel receives a letter from David and the pair embark on an odyssey through the backwoods of Maine to collect traditional songs and preserve them for posterity on wax cylinders. Lionel’s synaesthesia, which allows him to see colours when listening to music, is a steadfast travelling companion when life, once again, propels the men down different paths. Like a melody that lodges in the brain, Lionel continues to think about David and the time they spent together. Following a sun-kissed Roman holiday and an ill-fated dalliance with socialite Clarissa Roux (Emma Canning) beneath dreaming spires, Lionel doggedly seeks answers and a possible reunion.

Enriched with a voiceover from Chris Cooper as the older incarnation of Lionel, The History Of Sound has been flatteringly compared to Brokeback Mountain but Hermanus’s picture, for all its artful restraint, does not approach the raw emotional devastation of Ang Lee’s trek across the sheep-herding pastures of 1970s Wyoming. The muted colour palette and impeccable framing of Alexander Dynan’s cinematography mirror the understated excellence of the production and costume design.

Even in its quietest moments when the two-hour running time suddenly gains elasticity, there is an undeniable, beguiling beauty to a tortured world glimpsed through Hermanus’s eyes. Individually, Mescal and O’Connor have radiated white-hot emotion like supernovae in two of the finest LGBTQ romances of the past decade: All Of Us Strangers and God’s Own Country. Here, the actors harmonise appealingly and kindle aching tenderness but Shattuck’s adaptation of his own work fails to loudly convey the characters’ internal symphonies. Hushed stoicism caresses a heartstring that yearns to be plucked.

Find The History Of Sound in the cinemas

Sci-Fi

Mercy (12A)

Review: Human or AI: we all make mistakes. So says the beleaguered hero of director Timur Bekmambetov’s dystopian action thriller – a well-respected 2029 Los Angeles police detective presumed guilty until proven innocent of stabbing his wife to death in cold blood. Mercy orchestrates a frantic hunt for the truth in real-time and makes a few mistakes along the way to a satisfying but belaboured final judgment.

Police detective Chris Raven (Chris Pratt) regains consciousness from a drunken night of blood-stained chaos, strapped to a chair inside the Los Angeles headquarters of Mercy Capital Court. Motto: Swift Justice For All. He faces Maddox (Rebecca Ferguson), the artificial intelligence that acts as judge, jury and executioner in a city overrun with crime, drug use and homelessness. Chris sits accused of murdering his wife Nicole (Annabelle Wallis) in a jealous, alcohol-fuel crime of passion and has 90 minutes to gather evidence using voice commands and a touchscreen to prove his innocence or be sentenced to death by a lethal sonic pulse to the back of the cranium.

Maddox attributes a 97.5% degree of certainty to Chris’s guilt. To escape death, he must introduce sufficient reasonable doubt to persuade the judge to reduce the assessment below a 92% threshold. As the clock ticks down to his execution, Chris liaises with his partner, Detective Jacqueline Diallo (Kali Reis), to piece together clues while repeatedly assuring his daughter Britt (Kylie Rogers) that he is innocent. Unfortunately, Chris is harbouring secrets and even his AA sponsor, Rob (Chris Sullivan), who helped him cope with the death of a police partner (Kenneth Choi), fears the detective could be in denial about the terrible consequences of his actions.

Handcuffed to a 90-minute timer that ticks down relentlessly in one corner of the screen, Mercy is a confidently staged crime thriller that slowly pieces together events leading to Nicole’s death using CCTV recordings, private emails, social media posts, drones and footage conveniently uploaded to the cloud. Bekmambetov visualises a tsunami of communications, text and video files as overlapping screens that whoosh around Pratt in his high-tech executioner’s chair.

The actor is restrained by his wrists and ankles for almost the entire film and runs a gamut of emotions from tearful disbelief to glowering defiance as screenwriter Marco van Belle introduces a multitude of potential suspects and attempts to dissuade us from focusing on the most obvious candidate. The script’s heavy-handedness with foreshadowing diminishes the impact of rough justice and credibility is strained when Ferguson’s imperious AI overrides protocols to become complicit in an explosive showdown. Serious debate about the ethical implications of automated trials is sacrificed at the altar of slam-bang thrills.

Find Mercy in the cinemas

Drama

Saipan (15)

Review: In a 2002 interview with RTE News, shortly after he walked away from the captaincy of the Republic of Ireland’s World Cup squad, Roy Keane explained that he felt like he had been backed into a corner in his dispute with manager Mick McCarthy. “There was only going to be one winner,” Keane explained on camera, “and that was Mick, of course, and I understand that. He’s the manager.” These comments and a wealth of archive footage are skilfully woven into directors Lisa Barros D’Sa and Glenn Leyburn’s high-pressure fictionalised drama inspired by real-life events that gripped a nation.

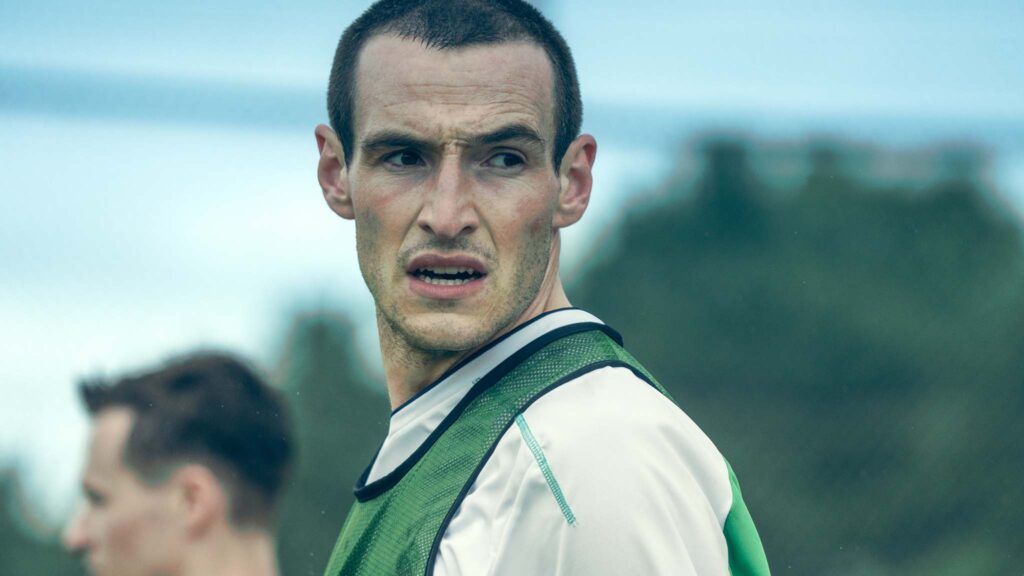

In the run-up to the 2002 FIFA World Cup hosted in South Korea and Japan, Roy (Eanna Hardwicke) sustains a knee injury playing for Manchester United and he trains hard to be fit in time to lead his country. Tension is evident between the captain and manager (Steve Coogan) from the moment Roy walks on to the team bus bound for the Pacific island of Saipan, where the squad will acclimatise to the heat and humidity and train ahead of a first-round match against Cameroon. Roy is unimpressed with the facilities. The air conditioning in his room malfunctions, the hotel serves platters of warm cheese sandwiches to players, the training pitch is likened to a car park, and someone forgot to order footballs for the team drills.

Other players are more interested in free access to a nearby golf course than preparing for warfare on the pitch, which flies in the face of Roy’s belief that you should “play to win… or why bother playing at all?” As captain, Roy feels compelled to speak up and demand the best for the team. Personalities clash and Roy announces his intention to leave. Mick Byrne (Peter McDonald) acts as a go-between but the island simply is not big enough for two bruised egos.

Saipan opens with a memorable clip of football correspondent Tony O’Donoghue reflecting that the media circus-fuelled disarray was “quite possibly the worst preparation any country has ever had for a World Cup finals”. D’Sa and Leyburn’s picture cuts between footage from the era and glossy dramatisation to distil weeks of discontent and miscommunication into the running time of a standard football match.

It is an entertaining and occasionally fiery kickabout and gently humorous scenes of Roy and Mick with their respective wives, Karen (Aoife Hinds) and Fiona (Alice Lowe), soften the key protagonists. Hardwicke curries the greatest sympathy as he presses the self-destruct button on Keane’s World Cup campaign while Coogan embraces McCarthy’s soft Yorkshire lilt with restraint. Paul Fraser’s screenplay builds tension gradually to the public shouting match that leads to Roy receiving his figurative red card. He thought it was all over, and it was.

Find Saipan in the cinemas