Thriller

The Housemaid (15)

Review: About 90 minutes into The Housemaid, A Simple Favour ringmaster Paul Feig’s psychological thriller adapted from the first book of Freida McFadden’s series of novels, the penny drops. With the most delectable and satisfying kerching. Until that narrative handbrake turn, we’ve been backseat passengers to a campy erotic potboiler about a down-on-her-luck heroine walking into the middle of a failing marriage and inadvertently positioning herself as the wealthy husband’s new mistress. Once Feig and screenwriter Rebecca Sonnenshine gear shift into delightfully deranged brinkmanship, anyone could end the film neatly enclosed within a white chalk outline.

Thirty-something ex-con Millie Calloway (Sydney Sweeney) has served her time for a righteous crime – in her eyes. She is on parole and looking for a job that will pay enough so she doesn’t have to live out of her car and wash each morning in public restrooms. Millie applies for a position as housemaid to Long Island housewife Nina Winchester (Amanda Seyfried) using bogus CV references that could easily be debunked with a few telephone calls and emails. “I really enjoy being a housemaid… for the right family of course,” coos Millie during the interview with the lady of the house.

Miraculously, Millie lands the job and is thrilled to live in the Winchester family’s attic as she cooks, cleans and tends to Nina, her husband Andrew (Brandon Sklenar) and their young daughter Cecelia (Indiana Elle), who oozes disdain beyond her tender years. Wife Nina exhibits wild mood swings that force Andrew to step in to protect Millie. The attraction between the married man and employee is palpable and Millie tries to resist self-sabotaging a job that pays well and keeps her on parole. Tension builds inside the gated home and enigmatic Italian groundskeeper Enzo (Michele Morrone) watches the unfolding tragedy from afar.

The Housemaid recalls lurid thrillers from the early 1990s and Feig clearly draws on his experience from A Simple Favour and its disappointing sequel to crank up the antagonism between feisty and resourceful female characters with markedly different bank balances. Sweeney and Seyfried are well matched. Adding some spice to the cocktail, Elizabeth Perkins sharpens her lacquered nails for a lacerating supporting performance as Andrew’s mother, who clearly doesn’t think any woman will be good enough for her boy.

Ignorance truly is bliss if you haven’t read McFadden’s book and aren’t prepared for the narrative rug pull that screenwriter Sonnenshine engineers with lip-smacking glee by returning to a seemingly throwaway scene and airing the extended version without editor Brent White’s timely intervention. Pacing sags as the film withholds its big reveal for longer than necessary but the final half hour is a shudder-inducing hallucination that takes any preconceptions to the cleaners.

Find The Housemaid in the cinemas

Drama

Marty Supreme (15)

Review: Timothee Chalamet wields a ping pong bat with verve and strokes his way into Oscar contention in a life-affirming drama loosely inspired by the life of New York Jewish table tennis prodigy Marty Reisman. Co-written by director Josh Safdie and longtime collaborator Ronald Bronstein, Marty Supreme globe-trots in the company of a fast-talking dreamer with unshakeable self-belief, who opens the film by impregnating his married lover to a euphoric burst of German synth-pop band Alphaville’s 1984 anthem, Forever Young.

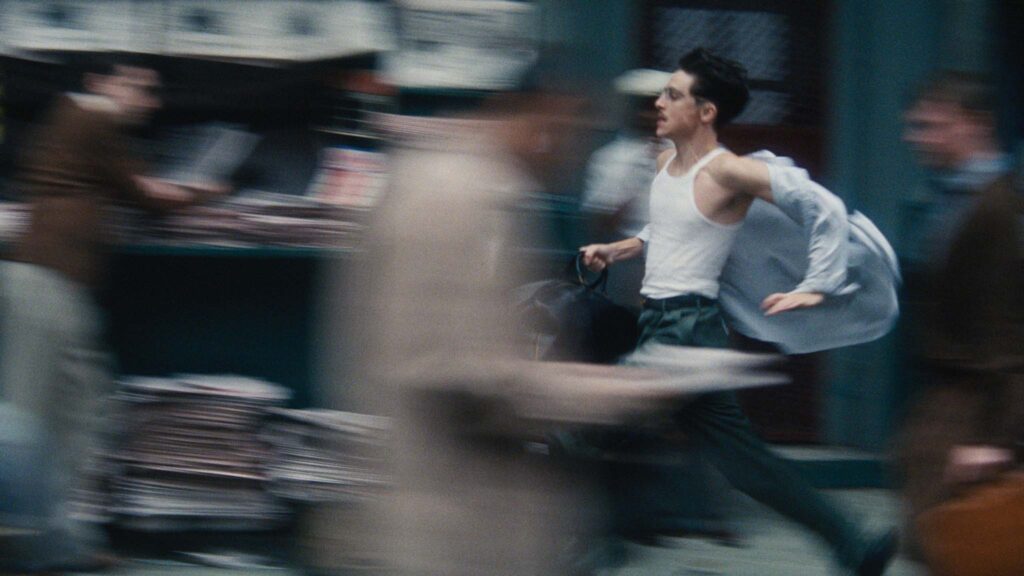

“Let us die young or let us live forever,” sings lead vocalist Marian Gold at the start of the second verse. That’s a mantra which Marty Mauser (Chalamet) can support. He sells shoes in 1952 New York in a Lower East Side store run by his uncle Murray (Larry “Ratso” Sloman) – one of the many doubters of Marty’s ambition to become a table tennis champion and represent his country with a ping pong paddle. Even his hypochondriac mother (Fran Drescher) dismisses his dream. “I could sell shoes to an amputee,” crudely boasts Marty, who intends to fly to London to compete in a tournament after he has engaged in enthusiastic sex with married sweetheart Rachel Mizler (Odessa A’zion) in the stockroom. When an advance of his wages fails to materialise, Marty “appropriates” money from the shop’s safe at gunpoint to buy a plane ticket.

He certainly makes an impact in London, promising gobsmacked reporters that he will demolish reigning Hungarian champion Bela Kletzki (Geza Rohrig). “I’m going do to Kletzski what Auschwitz couldn’t,” he quips, and adds that he is Jewish so his outburst is acceptable. Still in London, Marty becomes romantically entangled with retired actress Kay Stone (Gwyneth Paltrow), who is the wife of a pen company tycoon (Kevin O’Leary) that the cocksure wunderkind hopes will sponsor him to fly to Japan and seek revenge against their national sporting hero, Endo (Koto Kawaguchi).

Marty Supreme unfolds with less urgency than any of the title character’s ping pong matches and the 150-minute running time is more of a slog than it needs to be but director and co-writer Safie retains a firm grip on his material, eliciting robust supporting performances from A’zion and Paltrow. Chalamet has delivered some extraordinary portrayals in a relatively short period of time including a lovesick teenager in Call Me By Your Name, a struggling drug addict in Beautiful Boy and last year’s bravura embodiment of Bob Dylan in A Complete Unknown.

He scales new heights for Safdie, tightly coiled with nervous energy as his grifter doggedly proves naysayers wrong at a time when table tennis had no discernible profile in the United States. He’s a smash, even when the picture fitfully misdirects a verbal volley into the net.

Find Marty Supreme in the cinemas

Drama

Sentimental Value (15)

Review: Arts imitates and invigorates life in Joachim Trier’s deftly constructed drama about the heavy price of artistic expression on a family that feels more comfortable tackling fictional trauma than sifting through the smouldering wreckage of their real-life misdeeds. Slow-burning and contemplative by design, Sentimental Value is unafraid of awkward silences between characters who are unable to express themselves clearly. Simmering rage and resentment are palpable as a magnificent ensemble cast trades glancing blows and slowly manoeuvres into a place where some of them are open to listening and learning.

Renowned actress Nora Borg (Renate Reinsve) suffers from crippling bouts of stage fright that compel her to lock herself in her dressing room and miss her opening cue. After a nervy opening night performance with co-star and lover Jakob (Anders Danielsen Lie), Nora basks in congratulations from her sister Agnes (Inga Ibsdotter Lilleaas) and brother-in-law Even (Andreas Stoltenberg Granerud). Her heart is broken by the death of her psychotherapist mother Sissel and during the funeral reception, Nora and Anges’ estranged father Gustav Borg (Stellan Skarsgard) returns to offer his condolences.

The film director comes bearing a deeply personal film script that he hopes will resuscitate his career and rebuild bridges if Nora agrees to play the lead role. “I wrote it for you. You’re the only one who can play it,” he gruffly asserts. She rejects the clumsy olive branch and Gustav looks to fast-rising American actor Rachel Kemp (Elle Fanning) instead. She arrives in Oslo with two assistants (Catherine Cohen, Cory Michael Smith) and an intense curiosity about the real-life inspiration for the script. Making the film in the family home forces the Borgs to reopen old wounds. When Gustav eventually sits down with his two daughters for a candid discussion about his mistakes, he draws attention to how similar he is to Nora. “It’s hard to love someone who’s so full of rage,” he warns her.

Sentimental Value reunites Trier with Reinsve, Bafta-nominated star of his previous film The Worst Person In The World, for a deceptively simple and elegant study of the psychological damage that parents can unwittingly inflict on their offspring after a child deduces parents are flawed just like everyone else. Dialogue is razor-sharp and generously soaked in pain and regret, providing the central quartet of Reinsve, Skarsgard, Ibsdotter Lilleaas and Fanning with meaty material to chew on. Each of them has at least one standout scene of raw, unfiltered vulnerability.

The script incorporates a smattering of in-jokes for ardent fans of the big screen (Gustav’s present to his grandson is a highly inappropriate selection of arthouse films on DVD) but doesn’t descend into self-indulgent backslapping. The unshakeable, discomfiting truth emerges when you dare to turn the camera on yourself.

Find Sentimental Value in the cinemas