Horror

The Black Phone (15)

Review: Set in 1978 North Denver, the same year that Michael Myers materialised in the first Halloween, The Black Phone is a stylish and compact supernatural horror that promises more shocks and insidious dread than it ultimately delivers. Scott Derrickson, writer-director of Sinister, reunites with lead actor Ethan Hawke to conjure another mind-bending nightmare, adapted for the screen from Joe Hill’s short story with co-writer C Robert Cargill. As the title intimates, the film’s fantastical plot device is a wall-mounted, rotary dial telephone. The trilling receiver provides an otherworldly connection between vengeful phantoms of kidnapped and murdered boys and a new victim, who is being held hostage in a soundproofed cell.

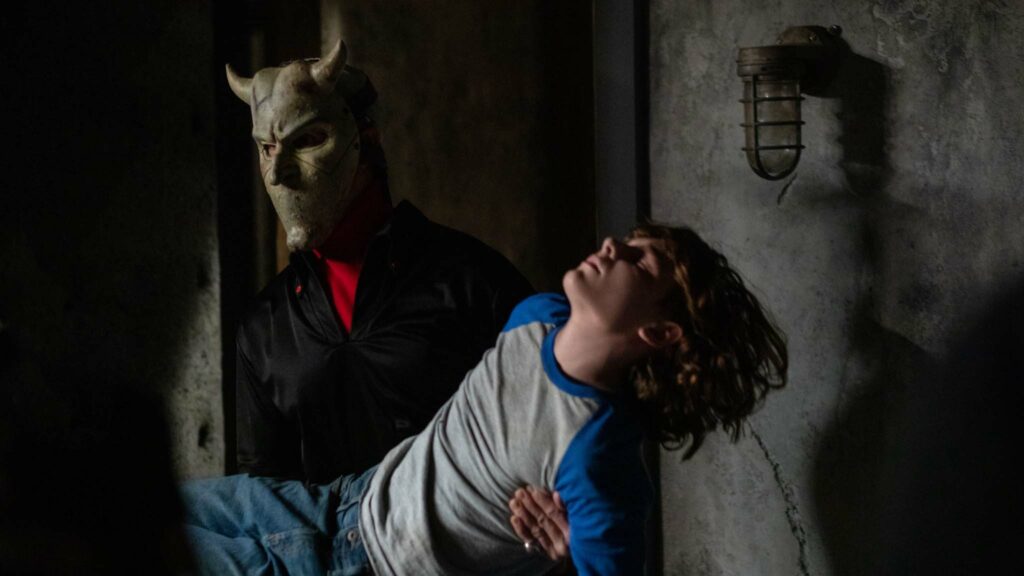

Hawke plays against type as the creepy antagonist, who does unspeakable things to his hostages and – in the film’s most quietly disturbing scene – sneaks down into his dungeon to watch one exhausted boy snatch a few hours of fitful sleep. The script doesn’t provide a back story for Hawke’s sick and twisted voyeur so he relies on acting mettle and a succession of disfigured, devilish face masks designed by prosthetic makeup artist Tom Savini to sustain menace without clear villainous motivation. Conventional jump scares hit their mark, accompanied by staccato blasts courtesy of composer Mark Korven.

A masked predator nicknamed The Grabber (Hawke) poses as a magician to lure unsuspecting children into the back of his Abracadabra-branded black van. Five youngsters including Bruce Yamada (Tristan Pravong) and Vance Hopper (Brady Hepner) vanish without trace despite the best efforts of Detective Wright (E Roger Mitchell) and partner Detective Miller (Troy Rudeseal) to identify a prime suspect. Their enquiries lead to a girl called Gwen Shaw (Madeleine McGraw), who claims to have prophetic dreams about the missing boys.

Behind closed doors, Gwen’s bullying, alcoholic father (Jeremy Davies) beats her for daring to disclose the psychic abilities inherited from her late mother. Shortly thereafter, The Grabber snatches Gwen’s bullied 13-year-old brother Finney (Mason Thames) and locks him in a dank basement with a soiled mattress. “Nothing bad is going to happen, I give you my word,” growls The Grabber to his deeply sceptical captive.

The Black Phone dials up palpable discomfort but there always seems to be a loose connection to skin-crawling distress. Thames delivers a compelling performance as a whelp faced with the realisation that he will probably die in subterranean gloom while McGraw scene-steals with her spunky urchin’s foul-mouthed outbursts. Derrickson’s use of graphic on-screen violence is sparing. Mindful of victims’ ages, he insinuates torture because the horrors that unfold out of shot in the dark are infinitely more chilling than anything he can drag kicking and screaming into the light.

Find The Black Phone in the cinemas

Drama

Elvis (12A)

Review: Wise men say only fools rush in. Baz Luhrmann, Australian director of Strictly Ballroom and Moulin Rouge!, appears to sing from the same hymn sheet because his visually extravagant biopic of Elvis Presley has a whole lotta shakin’ goin’ on with more than two-and-a-half hours of breathlessly choreographed musical performances, impeccable costume design and nostalgia-drenched spectacle.

Austin Butler delivers a scintillating, sexually charged performance as the jump-suited showman from Tupelo, Mississippi. Luhrmann’s camera fixates on his crotch, beginning with Presley’s first performance at the Louisiana Hayride, where “a skinny boy” in a loose-fitting pink suit metamorphoses into a pelvis-thrusting “superhero” and drives hordes of previously po-faced, unimpressed women in the audience into caterwauling harpies. You can’t help falling in love with Butler’s sweat-soaked embodiment of a socially conscious showman, who believed in lending his voice to the youth of the era and affecting change through his music.

Presley’s rise and fall is narrated by manager Colonel Tom Parker, an invidious presence at the mercy of gambling habits, who by his own voiceover admission could be considered “the villain of this here story”. As portrayed by Tom Hanks with a sing-song accent of intentionally curious European origin, Parker is an odious, opportunistic parasite who dazzles the Presley family with the promise of riches then turns his star talent against the people he should trust. “If you don’t do the business, the business will do you,” singer BB King (Kelvin Harrison Jr) warns good friend Presley before the true price of fame has reduced the charismatic dreamer to a physically exhausted husk, unable to fulfil his Las Vegas residency without an injection backstage from a doctor.

When we first see Elvis as a boy (played by Chaydon Jay), he is intoxicated by gospel church music and feels the spirit of a pastor, who sermonises, “When things are too dangerous to say, sing!” Presley takes this lesson to heart as he witnesses America’s bitter racial divisions while continuing to publicly support performers like BB King and Little Richard (Alton Mason). He falls under the spell of Priscilla (Olivia DeJonge), builds a home at Graceland for his parents Vernon (Richard Roxburgh) and Gladys (Helen Thomson) and slowly falls victim to Colonel Parker’s manipulations, rejecting a lucrative international tour because of security concerns stemming from high-profile assassinations including Martin Luther King and President John F Kennedy.

Elvis embodies Luhrmann’s filmmaking ethos of razzle-dazzling excess, energising each beautifully crafted frame with Mandy Walker’s ravishing cinematography, hyperkinetic camerawork and sumptuous period detail. Glimpsing Presley’s story from Parker’s perspective creates a narrative tug of war between the film’s most emotionally complex and colourful characters. The script can’t satisfyingly resolve that conflict – certain aspects are glossed over even with a luxurious 160-minute running time. Suspicious minds won’t be soothed.

Find Elvis in the cinemas